Higher housing costs offset higher wages in big cities, says new study

Historically, moving to a city has been seen as a pathway to greater economic mobility – as cities offer more and often higher-paying jobs. Still, migration from low-income to high-income states has slowed in recent years. In Forbes, Adam Millsap unpacks research from Jesse Rothstein, David Card, and Moises Yi investigating why. Read the full article.

From Marcy to Madison Square? The effects of growing up in public housing on early adult outcomes

The incidence and efficiency of land-value taxation

Building evidence on new pathways for economic opportunity

One land, many promises: the unequal consequences of childhood location

Research increasingly shows that opportunities for economic mobility are not equally distributed across different geographical areas; rather, in many countries, opportunities are becoming increasingly concentrated in a small number of regions. And a growing body of evidence is demonstrating the powerful impact that living in disadvantaged neighborhoods can have on one’s long-term, socioeconomic well-being. But to what degree do these “place effects” differ depending on other aspects of one’s upbringing, such as family income, or immigrant status? And how should policymakers consider demographic-specific impacts when designing policies aimed at promoting economic mobility?

Hadar Avivi, a recent PhD graduate of the Berkeley Economics Department, has spent the last few years investigating these granular aspects of place effects on children’s long-run economic outcomes, with support from O-Lab’s Place-Based Policy Initiative. As part of her job market paper, “One Land, Many Promises,” Avivi examines how place has impacted high-income and low-income families differently, and how it has affected immigrant and non-immigrant families differently. Her dataset includes over 1 million Soviet Jews who emigrated to Israel between 1989 and 2000, about 20% of whom were children under the age of 19 when they moved, a sample size large enough to allow Avivi to conduct a robust comparison of how neighborhood effects in childhood differ for different groups of children.

In order to carry out her analysis, Avivi leveraged comprehensive administrative data on the entirety of her sample - children and parents - collected by different Israeli ministries and consisting of tax records, education records, and national census data. Unlike in the United States, where statutes restrict data sharing across government departments, the Israeli Bureau of Statistics serves as a centralized body that is legally allowed to merge data from different ministries, contingent upon approval of a detailed proposal. “Very few countries have the possibility to merge different data sources like education records, tax records,” noted Avivi. This detailed dataset allowed her to incorporate demographic variables, like gender and country of origin, with information about date of immigration, place of residence, educational attainment, and income.

Strikingly, Avivi found substantial variation in the consequences of childhood location of residence across different cities and for different groups - children from high-income and low-income families and children who were born in Israel and those who emigrated during childhood. For high-income families, location effects are strongly and positively correlated: places with higher effects for immigrants are associated with higher effects for Israeli-born children. Among lower-income families, though, there was far more variation in which locations benefited immigrant children (and by how much) and which places benefited Israeli-born children. “The main, surprising finding is that… the correlation between the location effects for low-income immigrants versus Israeli-born children is practically zero,” said Avivi. This suggests that there is no single ladder of location quality, and the benefits from a childhood location of residence vary substantially across families.

For example:

Among immigrant families in the 25th percentile of the income distribution, relocating to the average Israeli city one year earlier increases their children's earnings at age 28 by $90 USD. By comparison, an additional year after relocating to the average Israeli city increases the income rank of children born in Israel by only $77 USD compared to spending one more year in Jerusalem.

Avivi’s paper also finds that location effects are more consequential for immigrant children at the higher end of the income distribution as well; overall, there is less variation in the way location impacts outcomes for Israeli-born children than for immigrant children.

For children from low-income families, moving at birth to a city with one standard deviation higher location effects increases the income of Israeli-born children by $1,370 at age 28, while increasing the income of immigrant children by $1,602 a year.

In order to better understand the disparate effects of location on immigrants and Israeli-born children of low- and high-income backgrounds, Avivi also investigated the relationships between location effects and city-level characteristics. On average, she found that larger cities are associated with more substantive long-run effects on children’s income, especially for immigrant families. And, for immigrant children, cities with very large or very small shares of immigrants were less likely to increase adult incomes. Cities with higher crime rates and welfare expenditures were more likely to be detrimental to children born in Israel, with more muted effects for low-income immigrants.

Finally, Avivi addresses the question of how policymakers could make use of these findings through a theoretical “moving to opportunity” policy, in which the government incentivizes low-income families to move to high-opportunity housing and neighborhoods. “While the first-best policy is personalized,” she says, “ethical and practical considerations [rule out] individually-targeted strategies because policymakers are not allowed to discriminate based on ethnic identity.” However, a “second-best” policy that simply ranks locations based on pooled weighted average estimates of outcomes can lead to worse outcomes for immigrant children (as they are a minority group, and therefore, the weighted average city effect puts, by construction, lower weight on their gains). To minimize the gap between the “first best” and “second best” policies, then, Avivi develops a novel “minimax” model that minimizes the potential harm to any group that might arise due to the inability to provide a targeted policy.

By expanding our understanding of how the long-term effects of location vary across groups, Avivi’s paper contributes to a growing body of evidence on the role of place in determining economic outcomes. The project, which received the 2024 O-Lab and Stone Center Prize for Excellence in Research on Economic Opportunity, also offers new insights into how policymakers can develop sophisticated and equitable policies in settings where the personalized first-best policy is infeasible. In September 2025, Avivi will continue her work as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at University College London, after spending one year as a postdoctoral fellow in the Industrial Relations Section at Princeton University.

The Case for Place-Based Policies

Event Recordings: 2023 Place-Based Policy Convening

Event recordings from the 2023 Convening on Regional Inequality & Place-Based Policy.

Property taxes, wealth inequality, and economic activity: lessons from São Paulo, Brazil

As wealth inequality continues to grow around the world, and as economic activity is increasingly geographically concentrated, there are wide-ranging debates in the economic literature about the role tax policy should play in promoting more equitable distribution of wealth and opportunity. In many rich countries, property taxes represent one of the most prominent tools for raising revenue and incentivizing economic activity in one location versus another. However, since property taxes are rarely used in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there is a gap in our understanding of how effectively they might work to affect disparities and economic activity in different contexts.

Brazil offers a unique case study for examining the role property taxes can play in reducing both geographic and racial wealth disparities in an LMIC context. With a robust data infrastructure for researchers to draw upon, and a recent tax reform aimed at creating more equitable distribution of economic activity, the country presents an opportunity to deepen our understanding of how individuals and firms respond to taxation and how taxation on high-value property can act as a tool for redirecting economic activity and promoting greater racial equity. Supported by O-Lab’s Place-Based Policy Initiative, Javier Feinmann, a PhD candidate in Economics, and his collaborators Roberto Hsu Rocha, Davi Moura, and Thiago Scott, are investigating these questions, drawing upon a rich dataset from the city of São Paulo.

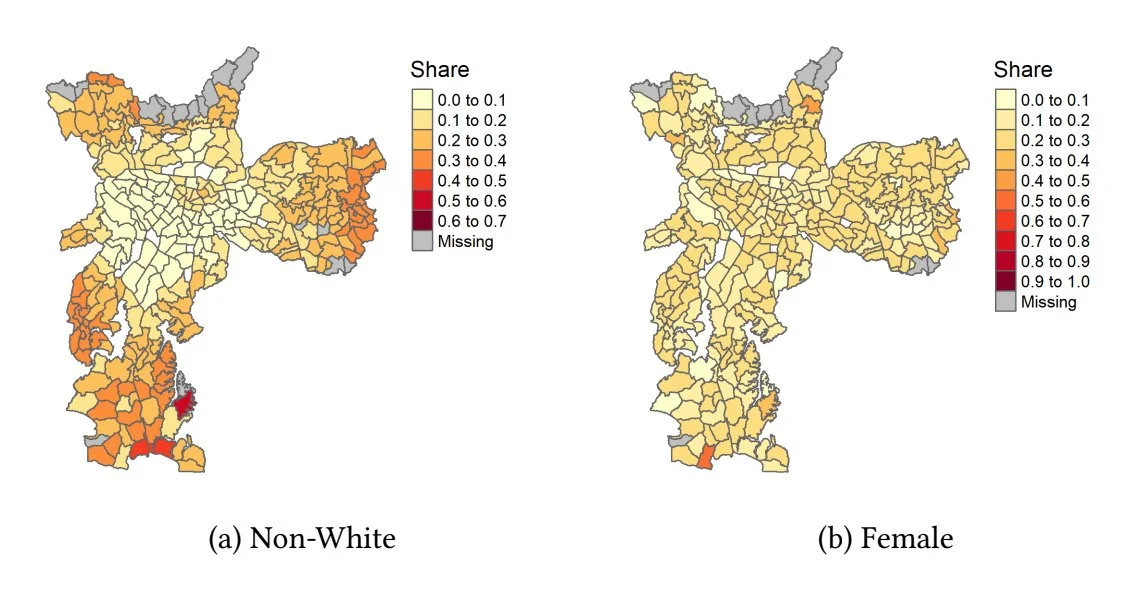

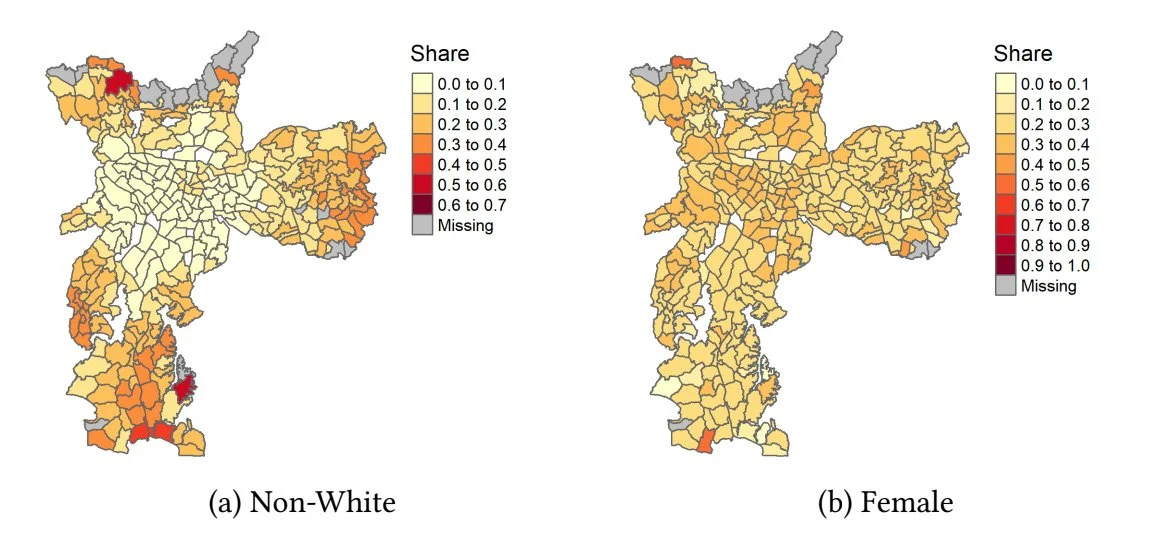

In the first stage of his research, Feinmann and his team are working to understand existing racial and gender disparities in wealth and property ownership in São Paulo. The researchers’ work is supported by a wealth of administrative data that allows him to create highly granular maps of property ownership and property tax rates. The project’s starting point is a database on annual property assessments in São Paulo. Using location-specific property identifiers, the team can spatially plot property values and tax rates throughout the city. Then, using a separate dataset which includes demographic information, they can link these properties to their owners, allowing race and gender identifiers to be incorporated into the map.

Figure 1: Geographical Segregation of São Paulo Property Ownership by Fiscal Zone

Figure 2: Geographical Segregation of São Paulo Wealth by Fiscal Zone

In this descriptive stage of his project, Javier and the team have confirmed disparities in property ownership for women and minority groups. In particular, the researchers find that across all property types and regions of São Paulo, women own fewer properties than men. The team has also found substantial racial disparities in property ownership; however, these are more variable across different regions of the city – likely resulting from existing regional segregation. In general, these gaps in gender and racial ownership are more pronounced among high-value properties.

In the next stage of his project, Feinmann will take a few extra steps to paint a more detailed picture of the distribution of property wealth and tax burdens in São Paulo. Specifically, since the state of São Paulo publicizes the registration of all businesses, Javier and coauthors are able to track the ultimate owners of registered firms that own property in São Paulo, including owner demographics. Then, the property wealth owned by firms can be proportionally assigned to ultimate owners. This novel approach provides a more comprehensive picture of who owns what in São Paulo. By accounting for individuals who own real estate through firms, this project also makes an important contribution to contemporary conversations by economists including Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez on how to accurately measure wealth held by the top percentiles.

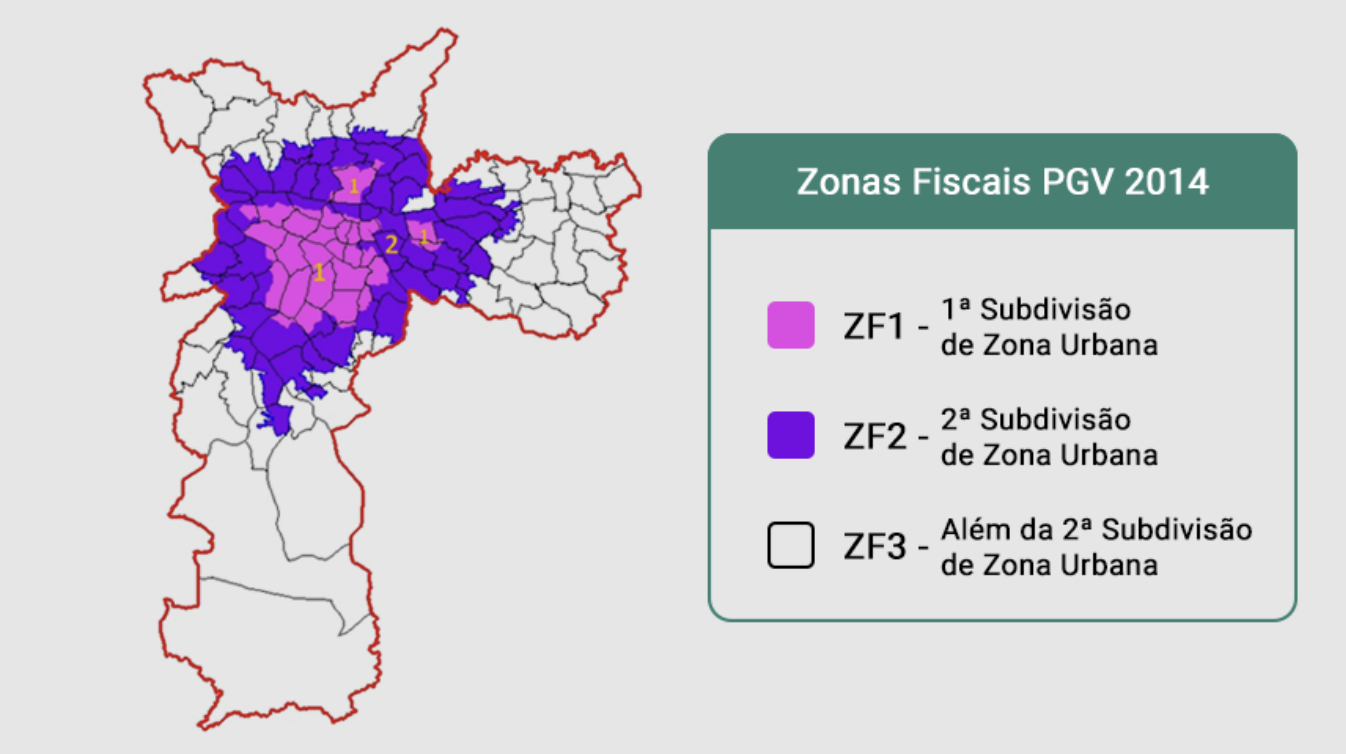

Figure 3: New fiscal zones instated by the 2014 tax reform.

Going forward, the researchers will use their findings as a basis for an analysis of how a major 2014 property tax reform in São Paulo affected economic activity and firm behavior in the city. The law in question divided São Paulo into three separate fiscal zones, and revised the property tax assessment formula to increase taxes on properties closest to the city’s wealthy central district. The intention of this change was to more equitably distribute property tax burdens in São Paulo – was the policy successful? What were the policy’s consequences for the location of economic activity – did it incentivize firm creation in less affluent, low-tax areas, or purely encourage existing firms to relocate? Upcoming stages of this project will explore these questions, and produce important new evidence on how regionally-targeted tax policies can influence racial and gender disparities in property ownership and wealth.

Enrico Moretti on Tech Hubs

MIT’s Sloan School of Management recently highlighted a new working paper from Enrico Moretti and coauthors that examines the balance between local productivity and local costs in research and development, and finds that the productivity gains from a density of scientific talent generally outweigh the additional costs. Still, their findings suggest that cities with exceptionally high talent density have labor and real estate costs that dwarf gains. Learn more about the study.

Patrick Kennedy and Harrison Wheeler Featured in the New York Times

O-Lab fellows Patrick Kennedy and Harrison Wheeler were featured in a recent New York Times article for their research on opportunity zone investments. Their study showed that a 2017 tax break for investors in economically struggling neighborhoods only increased investment in regions that were already becoming “richer and whiter,” with almost no investment in rural areas at all. Check out the article and read the full paper here.

Enrico Moretti on how costs affect living standards

A recent New York Times article explores how smaller towns and rural areas are seeing a new revival, as workers are enticed by lower costs of living. The piece mentions research from Enrico Moretti & Rebecca Diamond, which demonstrates significant differences in living standards based on geographic location, holding income constant. Read more here.

Enrico Moretti on the "Geography of Jobs"

A new piece in Forbes features Enrico Moretti’s research on the “geography of jobs” – in particular, how high rates of skilled labor inmigration and labor market clustering allow regions like Silicon Valley to continue growing in the face of high costs of living. Still, author Richard McGahey notes that this means low- and middle-income households struggle for a place in the housing market. Read more here.

An Introduction to the Place-Based Policy Initiative

Inequality and Place: Promoting Opportunity and Growth through Place Based Policy is working to build a research ecosystem around our world-class faculty working on issues of local and regional development to contribute new evidence to U.S. anti-poverty and economic mobility strategies.

Enrico Moretti on Remote Work and American Supercities

Enrico Moretti was recently interviewed in a Vox article on the future of American supercities post-pandemic. In the article, Moretti explains why people have historically tended to cluster geographically and why the benefits of agglomeration economies cannot fully be obtained from remote work.

California Housing and Homelessness in a Post-Covid Economy

Research Workshop on Place-Based-Policy and Urban Economics

Part of O-Lab’s Initiative on Inequality and Place, this virtual conference featured new work on topics such as urban migration patterns, foreclosures, state and local business incentives, and the impacts of place-specific taxes and tax credits.

Examining the Role of Housing Regulations in Exacerbating Wealth Inequality

The stark inequalities that have divided American society over the past three decades don’t just appear in people’s paychecks. They also increasingly determine where Americans live, how much preparation their children receive for the future, and whether workers can count on predictable and steady work from one week to the next.

Those are the sorts of diverse forms of social inequality that Joe LaBriola, a sixth-year sociology Ph.D. candidate, has built his academic career researching. He’s explored, for example, the role of worker power in reducing inequality in work hour instability. That paper, written with O-Lab affiliate Daniel Schneider, won LaBriola the 2018 IPUMS USA research award for best graduate student paper.

“The thing that jumped out to us is that right after the Great Recession, work hour volatility spiked for workers who were less educated and making the least amount of money,” LaBriola said. “Next we want to think about what we think is causing work hour volatility.”

LaBriola has been a prolific researcher, with five peer-reviewed publications and three chapters looking at subjects such as the effects of post-prison employment quality on recidivism, risk-taking at U.S. commercial banks, and how class gaps in parental investment in children change during the summer. His research is motivated by a recognition that the well-off enjoy more advantages at every stage of life, and that those at the bottom end of the workforce are too-often denied the security and benefits of full-time and predictable employment.

Another of LaBriola’s ongoing projects focused on how home ownership - and the attempts of some homeowners to restrict the development of new housing - has exacerbated wealth inequality. He points to research showing how the housing market increasingly shuts out low-income people who are hoping to build wealth through ownership. The “wealth gaps” that then arise can be just as consequential as income gaps, and only exacerbate and compound inequality over generations.

“If we build more housing supply, this could be something that will even out the playing field in terms of household wealth allotment,” LaBriola said. “Wealth inequality is not something that’s talked about as much as income equality, but it’s extremely important because wealth determines the amount of resources you have to move around in the world.”

For his research on housing development, he is merging national data on residential building permits going back to 1980 with data on household finances. He is also investigating the relationship between lawsuits over residential land use policy and housing development.

“I’m interested in whether homeowner opposition to new housing is a form of social closure,” LaBriola said. “Basically, people who already have a house they like - and who like the neighborhood they live in and don’t want to change - they might gain wealth by keeping it this way while everyone else suffers.”

Suburbanization and Black Employment

Research brief summarizing work by Conrad Miller.