How does increased minority enfranchisement impact public finance, preferences for public goods, and government fragmentation?

In 2013, the US Supreme Court issued a controversial ruling in the case of Shelby County v Holder, severely limiting the power of the federal government to enforce provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA). Before the ruling, changes to voting regulations by certain state and local governments were required to be “pre-cleared,” or deemed nondiscriminatory, before they were allowed to go into effect; after the ruling, it became the responsibility of disenfranchised voters to advocate for themselves and demonstrate that changes to voting laws were discriminatory.

This landmark ruling inspired a series of new studies examining the historical impacts of the VRA, in an effort to better understand its consequences and forecast the potential impacts of the Shelby decision. Raheem Chaudhry, a PhD candidate at the Goldman School of Public Policy, is leading one such study through his participation in the O-Lab’s Initiative on Racial Equity in the Labor Market.

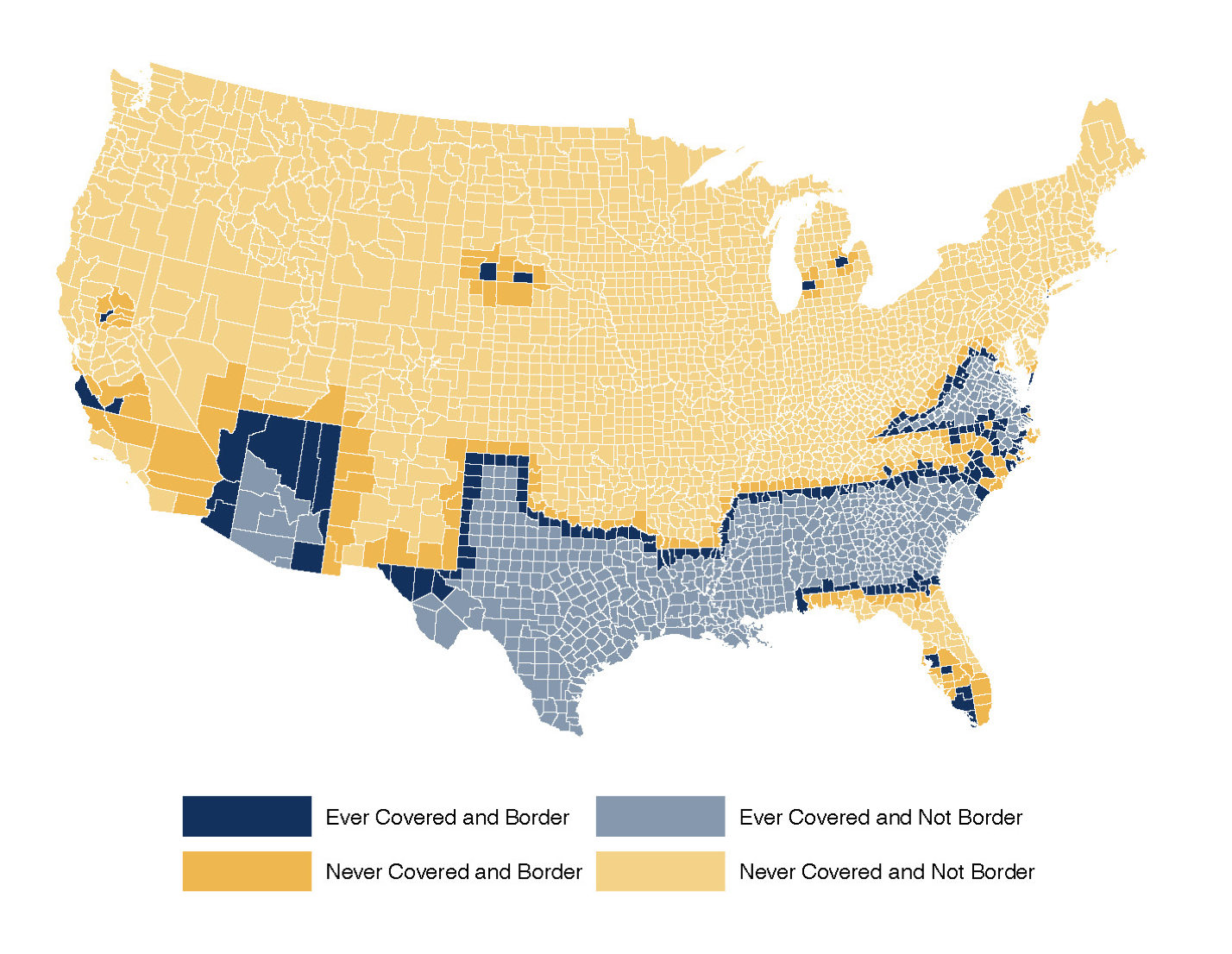

Raheem’s research focuses on how the VRA impacted local and state revenues, as well as municipal spending on a variety of services and programs – hypothesizing that higher turnout among Black voters would lead to increased spending on public goods. Raheem used data from the Census of Governments, a survey conducted every five years, to get a detailed picture of government spending at all levels, including cities, counties, and special districts. He then compared jurisdictions covered by special provisions of the VRA that applied to only especially discriminatory districts to similar, geographically-adjoined districts, in order to isolate the impact of these parts of the Act. Subsequently, he was able to compare differences in spending in districts impacted to those unaffected.

Initially, Raheem expected to find increases in public spending in those jurisdictions with substantial Black populations that were identified by the VRA as particularly discriminatory (those required to pre-clear any future changes to voting laws). In actuality, he found that counties with larger non-white population shares demonstrated relative declines in government revenues and expenditures — but why? Raheem’s working theory, informed in part by existing literature, sees these changes as a response to increased integration. By ruling out tax base changes as the cause of declining public spending — there were no significant changes in home values or incomes during the period of study — Chaudhry’s work offers a compelling narrative that voters in these districts were less inclined to finance increasingly integrated public resources. Further evidence in support of this theory can be seen in decreased levels of public school enrollment, particularly among white students, from 1968 to 1972 – which suggests that families turned to private school in response to increased integration. Raheem also found relative increases in government fragmentation amongst counties targeted by special provisions of the VRA with larger non-white populations. This finding follows existing literature, and suggests a mechanism by which increasingly integrated counties sought to maintain local control over public finances.

Raheem’s project complements a growing body of work among economists that shows the limits to migration as a tool for surmounting racial income inequality. His work adds an important focus, however, on the role of political power in the success or failure of policies promoting access to resources such as education, transportation, and more. “I think the way that people traditionally think about this is, ‘How do we move kids to high opportunity areas?’ But you can also think about, ‘How do you transform the places kids already live?’ And one way you can do that is through the political process.” While Chaudhry’s project does not find an explicit positive impact of the VRA on local public spending, it nevertheless has important lessons for policymakers. In particular, his work shows the powerful way in which racial backlash can undermine efforts to more equitably allocate public resources.