Narratives and destigmatization: the case of criminal record stigma in the labor market

David Harding wins Award for Advancing Institutional Excellence and Equity

Congratulations to Professor David Harding on his receipt of the 2024-2025 Chancellor's Award for Advancing Institutional Excellence and Equity! Harding, who chairs the Department of Sociology, has been instrumental in developing mentorship programs for formerly incarcerated scholars and trains early-career researchers in computational social science methods. Learn more about the award recipients.

Evaluating the effects of Chicago's Small Business Improvement Fund

One land, many promises: the unequal consequences of childhood location

Research increasingly shows that opportunities for economic mobility are not equally distributed across different geographical areas; rather, in many countries, opportunities are becoming increasingly concentrated in a small number of regions. And a growing body of evidence is demonstrating the powerful impact that living in disadvantaged neighborhoods can have on one’s long-term, socioeconomic well-being. But to what degree do these “place effects” differ depending on other aspects of one’s upbringing, such as family income, or immigrant status? And how should policymakers consider demographic-specific impacts when designing policies aimed at promoting economic mobility?

Hadar Avivi, a recent PhD graduate of the Berkeley Economics Department, has spent the last few years investigating these granular aspects of place effects on children’s long-run economic outcomes, with support from O-Lab’s Place-Based Policy Initiative. As part of her job market paper, “One Land, Many Promises,” Avivi examines how place has impacted high-income and low-income families differently, and how it has affected immigrant and non-immigrant families differently. Her dataset includes over 1 million Soviet Jews who emigrated to Israel between 1989 and 2000, about 20% of whom were children under the age of 19 when they moved, a sample size large enough to allow Avivi to conduct a robust comparison of how neighborhood effects in childhood differ for different groups of children.

In order to carry out her analysis, Avivi leveraged comprehensive administrative data on the entirety of her sample - children and parents - collected by different Israeli ministries and consisting of tax records, education records, and national census data. Unlike in the United States, where statutes restrict data sharing across government departments, the Israeli Bureau of Statistics serves as a centralized body that is legally allowed to merge data from different ministries, contingent upon approval of a detailed proposal. “Very few countries have the possibility to merge different data sources like education records, tax records,” noted Avivi. This detailed dataset allowed her to incorporate demographic variables, like gender and country of origin, with information about date of immigration, place of residence, educational attainment, and income.

Strikingly, Avivi found substantial variation in the consequences of childhood location of residence across different cities and for different groups - children from high-income and low-income families and children who were born in Israel and those who emigrated during childhood. For high-income families, location effects are strongly and positively correlated: places with higher effects for immigrants are associated with higher effects for Israeli-born children. Among lower-income families, though, there was far more variation in which locations benefited immigrant children (and by how much) and which places benefited Israeli-born children. “The main, surprising finding is that… the correlation between the location effects for low-income immigrants versus Israeli-born children is practically zero,” said Avivi. This suggests that there is no single ladder of location quality, and the benefits from a childhood location of residence vary substantially across families.

For example:

Among immigrant families in the 25th percentile of the income distribution, relocating to the average Israeli city one year earlier increases their children's earnings at age 28 by $90 USD. By comparison, an additional year after relocating to the average Israeli city increases the income rank of children born in Israel by only $77 USD compared to spending one more year in Jerusalem.

Avivi’s paper also finds that location effects are more consequential for immigrant children at the higher end of the income distribution as well; overall, there is less variation in the way location impacts outcomes for Israeli-born children than for immigrant children.

For children from low-income families, moving at birth to a city with one standard deviation higher location effects increases the income of Israeli-born children by $1,370 at age 28, while increasing the income of immigrant children by $1,602 a year.

In order to better understand the disparate effects of location on immigrants and Israeli-born children of low- and high-income backgrounds, Avivi also investigated the relationships between location effects and city-level characteristics. On average, she found that larger cities are associated with more substantive long-run effects on children’s income, especially for immigrant families. And, for immigrant children, cities with very large or very small shares of immigrants were less likely to increase adult incomes. Cities with higher crime rates and welfare expenditures were more likely to be detrimental to children born in Israel, with more muted effects for low-income immigrants.

Finally, Avivi addresses the question of how policymakers could make use of these findings through a theoretical “moving to opportunity” policy, in which the government incentivizes low-income families to move to high-opportunity housing and neighborhoods. “While the first-best policy is personalized,” she says, “ethical and practical considerations [rule out] individually-targeted strategies because policymakers are not allowed to discriminate based on ethnic identity.” However, a “second-best” policy that simply ranks locations based on pooled weighted average estimates of outcomes can lead to worse outcomes for immigrant children (as they are a minority group, and therefore, the weighted average city effect puts, by construction, lower weight on their gains). To minimize the gap between the “first best” and “second best” policies, then, Avivi develops a novel “minimax” model that minimizes the potential harm to any group that might arise due to the inability to provide a targeted policy.

By expanding our understanding of how the long-term effects of location vary across groups, Avivi’s paper contributes to a growing body of evidence on the role of place in determining economic outcomes. The project, which received the 2024 O-Lab and Stone Center Prize for Excellence in Research on Economic Opportunity, also offers new insights into how policymakers can develop sophisticated and equitable policies in settings where the personalized first-best policy is infeasible. In September 2025, Avivi will continue her work as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at University College London, after spending one year as a postdoctoral fellow in the Industrial Relations Section at Princeton University.

Racial discrimination in the New Deal’s Agricultural Adjustment Act

In the early years of the Great Depression, US farmers faced an emergency, as the prices for their goods plummeted due to excess supply. In order to restore farmers’ purchasing power and stabilize prices, President Roosevelt passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933, which, among other things, offered incentives to farmers who did not plant basic crops.

While the AAA was successful in achieving some of its goals, its design and implementation heavily favored white farmers and landowners, while preventing many Black farmers and sharecroppers from collecting benefits they were owed. This has led historians to suggest that discrimination within the program helped drive many Black farmers out of agriculture entirely, although there have been no empirical analyses documenting the impact of the program on Black families’ economic outcomes.

Sheah Deilami-Nugent, a third year student in Berkeley’s Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, is aiming to fill this gap in the literature by investigating how the design of the AAA impacted occupational outcomes and decisions to relocate among Black farmers. Deilami’s interest in the topic was motivated in part by a podcast episode, in which a Black farmer described his struggles in accessing credit. As she dug deeper into this history, Deilami found the AAA repeatedly cited as one of the major sources of discrimination that led to land losses for Black farmers.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act was passed in 1933 to reduce the supply of key crops – corn, cotton, milk, peanuts, rice, tobacco, and wheat – by providing direct payments to farmers who agreed to limit their production of these crops. And while there were no explicitly discriminatory elements in the language of the act itself, its implementation opened two critical doors for discrimination against Black farmers.

First, AAA payments were processed through an existing structure of county-level agricultural extension offices. Extension agents were responsible for both educating farmers on how to claim their benefits and appointing the members of the county committees – consisting of primarily wealthy, white landowners – which processed appeals and complaints from farmers. White extension agents notoriously did not work with Black farmers and sharecroppers – and, while some counties had Black extension agents, the role of Black agents was focused almost entirely on education of Black farmers, and they generally did not have the same power as white agents to appoint committee members. So Black farmers were less likely to be informed about the act and their eligibility, and were less likely to receive a fair hearing when complaints arose.

The process of distributing payments also created incentives for discrimination. Specifically, payments were made exclusively to landowners (often white), who in many cases did not pass on any benefits to sharecroppers and tenant farmers (often Black). Because the complaint process was effectively closed to Black farmers, there was little recourse for Black tenant farmers and sharecroppers to claim the benefits that they were owed.

Deilami hypothesizes that differences in the racial makeup of county-level extension offices may have led to different rates of farmers successfully receiving AAA payments. Specifically, she is exploring whether Black farmers with access to Black extension agents in their counties might have known more about the policy, and had more recourse to receive funds. To investigate this, her project is leveraging agricultural and individual-level census data, AAA spending data, and data on county extension agents and committees. Deilami is still in the process of gathering and analyzing this data – an undertaking which led her to the National Archives in Maryland earlier this year. “I have extension agent data from Louisiana, but I need it for the rest of the Southeast. I might have to go to a few more places to get that data — but it’s amazing to work with archival data, and hold documents that only a few people have held. As a graduate student, you have the privilege to work on these kinds of projects that take a longer amount of time.” Deilami’s goal is to use data on the demographics of extension agents as a source of variation that may be correlated with occupational exit and migration, in addition to long-run outcomes like wealth and income.

While previous work has examined the general effects of the AAA, Deilami’s focus on its racial impacts will contribute important new evidence on the drivers of the Great Migration and how local institutions like the AAA’s county committees can impact long-term outcomes for the people they govern. Deilami also sees her project as well-positioned to catalog the scale of damages done by discriminatory policies, as she notes “This land back in the 1900s that could’ve generated a lot of intergenerational wealth…[that opportunity] is just gone now…the damage has been done.” By contributing to the growing evidence base on the long-term harms of federal discrimination, Deilami’s project provides essential perspective on the importance of equity-oriented policy and implementation.

Pat Kline + Chris Walters on employment discrimination in the New York Times

From 2019-2021, Pat Kline and Chris Walters sent 80,000+ fake resumes to Fortune 500 companies, conveying racial and gender characteristics through distinctive applicant names to understand discriminatory hiring behavior. Explore this article from the New York Times to learn more about the study’s results.

The Long-Term Economic Impacts of Federal Employment Segregation

Research brief summarizing work by Abhay Aneja and Guo Xu.

Michael Reich in Berkeley News

“A minimum wage increase doesn’t kill jobs,” says Michael Reich. A new article from Berkeley News highlights a recent working paper by Reich and coauthors at IRLE on the impact of minimum wage laws on small businesses, which finds that higher wages eases employee recruitment and retention. Read the news piece here, and check out the full working paper.

How does increased minority enfranchisement impact public finance, preferences for public goods, and government fragmentation?

In 2013, the US Supreme Court issued a controversial ruling in the case of Shelby County v Holder, severely limiting the power of the federal government to enforce provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA). Before the ruling, changes to voting regulations by certain state and local governments were required to be “pre-cleared,” or deemed nondiscriminatory, before they were allowed to go into effect; after the ruling, it became the responsibility of disenfranchised voters to advocate for themselves and demonstrate that changes to voting laws were discriminatory.

This landmark ruling inspired a series of new studies examining the historical impacts of the VRA, in an effort to better understand its consequences and forecast the potential impacts of the Shelby decision. Raheem Chaudhry, a PhD candidate at the Goldman School of Public Policy, is leading one such study through his participation in the O-Lab’s Initiative on Racial Equity in the Labor Market.

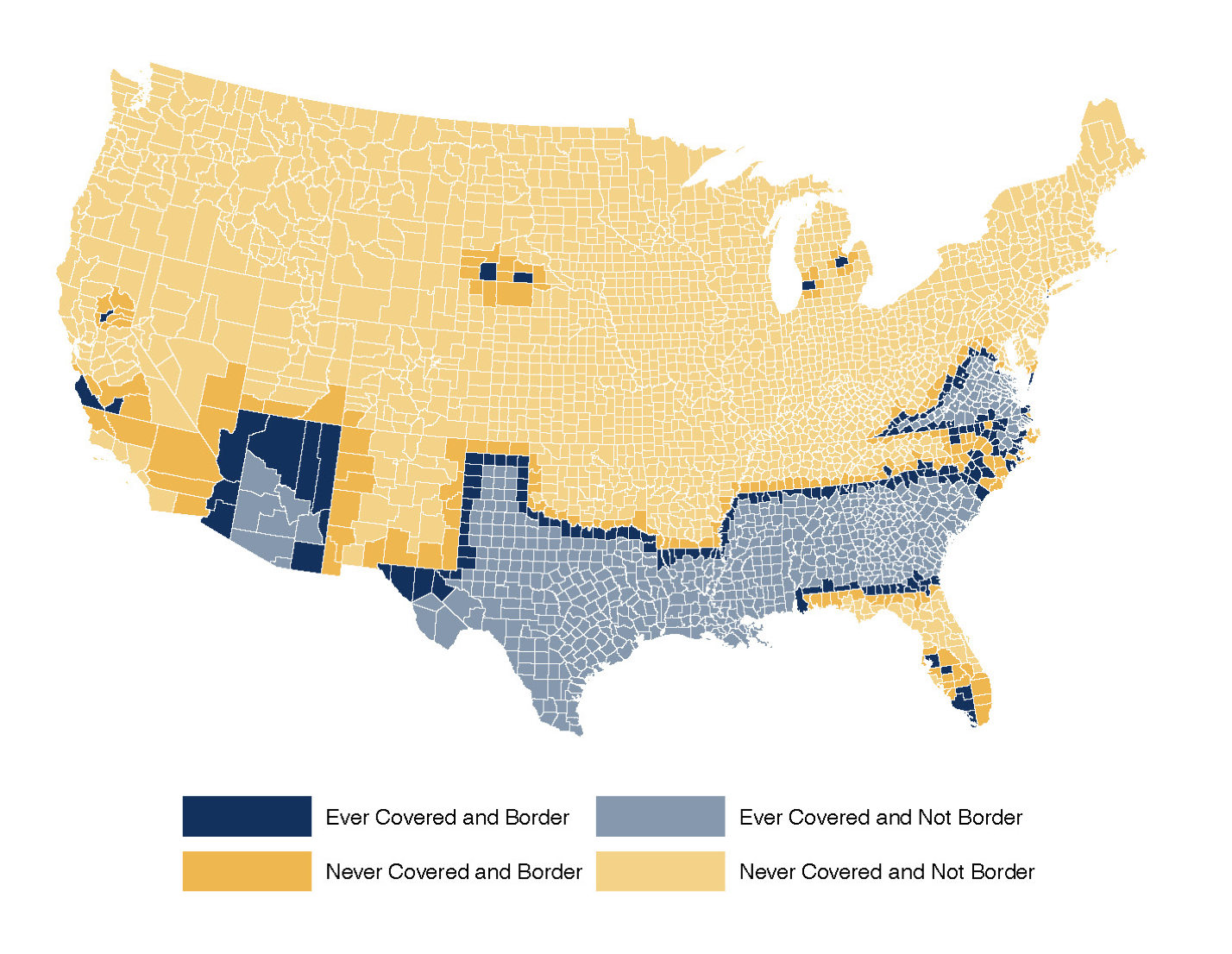

Raheem’s research focuses on how the VRA impacted local and state revenues, as well as municipal spending on a variety of services and programs – hypothesizing that higher turnout among Black voters would lead to increased spending on public goods. Raheem used data from the Census of Governments, a survey conducted every five years, to get a detailed picture of government spending at all levels, including cities, counties, and special districts. He then compared jurisdictions covered by special provisions of the VRA that applied to only especially discriminatory districts to similar, geographically-adjoined districts, in order to isolate the impact of these parts of the Act. Subsequently, he was able to compare differences in spending in districts impacted to those unaffected.

Initially, Raheem expected to find increases in public spending in those jurisdictions with substantial Black populations that were identified by the VRA as particularly discriminatory (those required to pre-clear any future changes to voting laws). In actuality, he found that counties with larger non-white population shares demonstrated relative declines in government revenues and expenditures — but why? Raheem’s working theory, informed in part by existing literature, sees these changes as a response to increased integration. By ruling out tax base changes as the cause of declining public spending — there were no significant changes in home values or incomes during the period of study — Chaudhry’s work offers a compelling narrative that voters in these districts were less inclined to finance increasingly integrated public resources. Further evidence in support of this theory can be seen in decreased levels of public school enrollment, particularly among white students, from 1968 to 1972 – which suggests that families turned to private school in response to increased integration. Raheem also found relative increases in government fragmentation amongst counties targeted by special provisions of the VRA with larger non-white populations. This finding follows existing literature, and suggests a mechanism by which increasingly integrated counties sought to maintain local control over public finances.

Raheem’s project complements a growing body of work among economists that shows the limits to migration as a tool for surmounting racial income inequality. His work adds an important focus, however, on the role of political power in the success or failure of policies promoting access to resources such as education, transportation, and more. “I think the way that people traditionally think about this is, ‘How do we move kids to high opportunity areas?’ But you can also think about, ‘How do you transform the places kids already live?’ And one way you can do that is through the political process.” While Chaudhry’s project does not find an explicit positive impact of the VRA on local public spending, it nevertheless has important lessons for policymakers. In particular, his work shows the powerful way in which racial backlash can undermine efforts to more equitably allocate public resources.

Conrad Miller on Job Suburbanization & Black Employment

In a National Bureau of Economic Research video feature, Conrad Miller breaks down his paper at the intersection of racial equity, labor, and geography: “When Work Moves: Suburbanization and Black Employment.” Miller finds that highway construction resulted in job suburbanization, increasing the employment gap between black and white workers. Watch the video here.

Research in Review: The Minimum Wage

Promoting Economic Well-Being During COVID-19 through the Unemployment Insurance Program

Literature review by Ellora Derenoncourt, Claire Montialoux, and Joseph Broadus.

Ellora Derenoncourt on Shortcomings of the Great Migration

A new piece from Inequality.org cites research by affiliate Ellora Derenoncourt to explain the shortcomings of the Great Migration. Resulting from the racist violence of 1919’s “Red Summer,” in addition to policies driving de-industrialization, ghettoization of African Americans, white flight, and mass incarceration, outcomes for third-generation Black children in the North today look no better than outcomes for their Southern counterparts. Read the article here.

Ellora Derenoncourt on Racial Wealth Inequality

Despite progress made since the civil rights movement, efforts toward reducing racial wealth inequality are stalling, highlights NPR Planet Money. The latest edition of the newsletter features new research from affiliate Ellora Derenoncourt and coauthors that constructs the first continuous dataset on wealth inequality between Black and white Americans, dating back to 1860. Read more here.

New Student Research Builds Evidence on Different Dimensions of Inequality

Program Manager Joe Broadus recaps new student research on how employment policy can advance or reduce racial disparities in the labor market and promote equitable economic growth.

Jesse Rothstein on Job Prospects for the College-Educated

College-educated workers struggle to reach the middle class more so than previous generations, impacting politics and labor activism. A New York Times article by Noam Scheiber discusses associated consequences for unionization, featuring research from Jesse Rothstein that finds that job prospects for the college-educated had not recovered ten years after the Great Recession. Read more here.

Ziad Obermeyer on Artificial Intelligence in Medicine

Ziad Obermeyer was recently featured on an episode of Freakonomics MD, in which he shared new research finding that artificial intelligence may be better equipped to predict heart attack risk than doctors. Still, Obermeyer emphasizes shortcomings – noting that many Ai algorithms have been proven to exhibit significant racial biases. Read more here.

David Card Awarded Nobel Prize in Economics

On October 11th, David Card was awarded the 2021 Nobel Prize in Economics along with Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens. Card has pushed the boundaries of the field of labor economics for over three decades, including his landmark 1993 paper with Alan Krueger on a New Jersey minimum wage increase.

Read more about the award and read his 1993 paper here.

Do Financial Concerns Make Workers Less Productive?

Research brief summarizing work by Supreet Kaur, Sendhil Mullainathan, Suanna Oh, and Frank Schilbach.