The long-term effects of entering the workforce during a recession

Economic recessions create an array of immediate and widespread challenges for workers, exerting labor market pressures that lead to layoffs and make it difficult to find a job and earn enough to make ends meet. These conditions can also lead to long-term consequences for those whose first entry into the workforce coincides with a recession or economic downturn. With increasing access to high-quality administrative data spanning decades, there is a growing body of research documenting the scale of these consequences (referred to as “economic scarring”) on one’s long-term life trajectory.

Cesia Sanchez, who received her PhD from UC Berkeley’s Economics Department in May 2024, is making important new contributions to this literature. In part, her interest stems from a desire to understand the experiences that shaped her upbringing, including the impact the subprime mortgage crisis had on her family. During her undergraduate studies at Texas A&M, Sanchez realized, “I need to keep up with econ because it's going to help me understand my life experiences. In my principles of macroeconomics course, I learned what being seasonally employed meant. We studied the bursting of the real estate bubble. That class taught me that all of my life experiences could inform research questions that I’ve studied.”

Sanchez’s dissertation, The Effect of Early Economic Conditions on Young Adults’ Transition Into Adulthood and their Occupational Characteristics, offers new ways of looking at the long-term impacts of exposure to economic downturns early in life. Specifically, while previous work in this field has largely examined how labor market trends affect college graduates, Sanchez focuses additionally on high school graduates. Her analysis also considers a wider array of variables (in addition to standard outcomes related to earnings and employment) in order to understand how recessions impact the transition into adulthood more broadly, and what consequences economic downturns have for the quality of employment one can access down the road.

In the first part of her paper, Sanchez uses data from the American Community Survey, covering 19 to 30 year olds between 2006 and 2021, to estimate the effect of economic conditions on a variety of variables indicative of transition to adulthood – including employment rates, earnings, living arrangements, marriage, and educational attainment. As a measure of exposure to recessionary conditions, she takes the unemployment rate at age 18 for each member of her sample, rather than focusing on a labor market entry point of age 22, or post-college graduation. By beginning her analysis at the point of high school graduation, rather than college graduation, Sanchez can estimate how recessions influence the way young people make decisions – about pursuing careers, post-secondary education, and alternatives like trade school – and how these choices impact future job quality.

Corroborating findings from past research, Sanchez finds that those who experience high unemployment rates at age 18 are less likely to be employed up to age 23, and are more likely to have very low earnings throughout their twenties, relative to their counterparts who come of age during a period of low unemployment. In a new contribution to the evidence on scarring effects, Sanchez’s paper also documents that these same individuals are much more likely to live with their parents throughout their twenties. Consequences for marriage and college attendance, however, are a bit more mixed. High unemployment rates at age 18 have a polarizing effect on the decision to marry: those who would’ve otherwise married early do so even earlier, whereas those who would’ve married later delay. Similarly, high unemployment rates accelerate college enrollment, but do not spur enrollment from students who would not have attended college in more favorable economic conditions.

Source: Autor, David H., and David Dorn. 2013. "The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the US Labor Market." American Economic Review, 103 (5): 1553–97.

If young people’s employment and earnings are negatively affected by recessions, what consequences might economic conditions have for the quality of jobs they access? The second part of Sanchez’s dissertation examines this question, with a focus on what kinds of skills are required of jobseekers. While past research on scarring effects has investigated outcomes for job quality, Sanchez takes a somewhat different approach in her measurements of job quality. “[In past literature] working in a higher quality job was typically defined as working in a job within the top five highest-paying categories of your college major – again, thinking about those people who graduated college,” she said. Rather than follow this definition, Sanchez draws from research on the “job polarization phenomenon,” which describes why economic downturns tend to result in job losses in middle-skilled occupations. Sanchez employs “task intensity measures” from this literature, designating occupations as primarily routine, manual, or abstract.

Sanchez expected to find that graduating from high school in a time of high unemployment would lead to (a) an increased likelihood of working in a primarily manual or abstract occupation, and (b) a decreased likelihood of working in routine occupations. This hypothesis aligns with the job polarization phenomenon, which suggests that recessionary conditions put the most pressure on availability of middle-skilled, or “routine” occupations, as companies can most easily automate these job functions. Sanchez’s analysis confirmed these hypotheses for routine jobs (decreased likelihood) and abstract jobs (increased likelihood), but it also suggested that graduating under recessionary conditions reduced employment in manual jobs as well – a surprising finding to her, given that high school graduates are relatively low-skilled. “That's a puzzle that I'd like to understand – why do those effects not match the job polarization phenomenon?”

In August 2024, Sanchez joined Baylor University’s Department of Economics as a Clinical Assistant Professor, where she’ll continue her research on the long-term consequences of economic and labor market conditions on young people’s lives. In particular, Sanchez hopes to more thoroughly investigate why recessions seem to lead to higher-quality jobs for high school graduates. She takes her findings as suggestive evidence of an acceleration effect that recessions might produce for high school graduates: facing the labor market consequences of a recession, new graduates rapidly pursue education - in particular, trade certificates - that quickly result in employment in abstract-oriented, high-quality jobs. By comparison, jobseekers who graduate from college in a recession may not have anticipated struggling to find a job, and may have therefore chosen career paths that are less well-suited to recessionary conditions. “Experiencing a recession at the age of 21, you hadn't been in the job search at the age of 18 to really think through, ‘What is the economy going to demand by the time that I graduate?’ And I think that's what's happening. It’s something that I want to study more to fully complete this paper.”

One land, many promises: the unequal consequences of childhood location

Research increasingly shows that opportunities for economic mobility are not equally distributed across different geographical areas; rather, in many countries, opportunities are becoming increasingly concentrated in a small number of regions. And a growing body of evidence is demonstrating the powerful impact that living in disadvantaged neighborhoods can have on one’s long-term, socioeconomic well-being. But to what degree do these “place effects” differ depending on other aspects of one’s upbringing, such as family income, or immigrant status? And how should policymakers consider demographic-specific impacts when designing policies aimed at promoting economic mobility?

Hadar Avivi, a recent PhD graduate of the Berkeley Economics Department, has spent the last few years investigating these granular aspects of place effects on children’s long-run economic outcomes, with support from O-Lab’s Place-Based Policy Initiative. As part of her job market paper, “One Land, Many Promises,” Avivi examines how place has impacted high-income and low-income families differently, and how it has affected immigrant and non-immigrant families differently. Her dataset includes over 1 million Soviet Jews who emigrated to Israel between 1989 and 2000, about 20% of whom were children under the age of 19 when they moved, a sample size large enough to allow Avivi to conduct a robust comparison of how neighborhood effects in childhood differ for different groups of children.

In order to carry out her analysis, Avivi leveraged comprehensive administrative data on the entirety of her sample - children and parents - collected by different Israeli ministries and consisting of tax records, education records, and national census data. Unlike in the United States, where statutes restrict data sharing across government departments, the Israeli Bureau of Statistics serves as a centralized body that is legally allowed to merge data from different ministries, contingent upon approval of a detailed proposal. “Very few countries have the possibility to merge different data sources like education records, tax records,” noted Avivi. This detailed dataset allowed her to incorporate demographic variables, like gender and country of origin, with information about date of immigration, place of residence, educational attainment, and income.

Strikingly, Avivi found substantial variation in the consequences of childhood location of residence across different cities and for different groups - children from high-income and low-income families and children who were born in Israel and those who emigrated during childhood. For high-income families, location effects are strongly and positively correlated: places with higher effects for immigrants are associated with higher effects for Israeli-born children. Among lower-income families, though, there was far more variation in which locations benefited immigrant children (and by how much) and which places benefited Israeli-born children. “The main, surprising finding is that… the correlation between the location effects for low-income immigrants versus Israeli-born children is practically zero,” said Avivi. This suggests that there is no single ladder of location quality, and the benefits from a childhood location of residence vary substantially across families.

For example:

Among immigrant families in the 25th percentile of the income distribution, relocating to the average Israeli city one year earlier increases their children's earnings at age 28 by $90 USD. By comparison, an additional year after relocating to the average Israeli city increases the income rank of children born in Israel by only $77 USD compared to spending one more year in Jerusalem.

Avivi’s paper also finds that location effects are more consequential for immigrant children at the higher end of the income distribution as well; overall, there is less variation in the way location impacts outcomes for Israeli-born children than for immigrant children.

For children from low-income families, moving at birth to a city with one standard deviation higher location effects increases the income of Israeli-born children by $1,370 at age 28, while increasing the income of immigrant children by $1,602 a year.

In order to better understand the disparate effects of location on immigrants and Israeli-born children of low- and high-income backgrounds, Avivi also investigated the relationships between location effects and city-level characteristics. On average, she found that larger cities are associated with more substantive long-run effects on children’s income, especially for immigrant families. And, for immigrant children, cities with very large or very small shares of immigrants were less likely to increase adult incomes. Cities with higher crime rates and welfare expenditures were more likely to be detrimental to children born in Israel, with more muted effects for low-income immigrants.

Finally, Avivi addresses the question of how policymakers could make use of these findings through a theoretical “moving to opportunity” policy, in which the government incentivizes low-income families to move to high-opportunity housing and neighborhoods. “While the first-best policy is personalized,” she says, “ethical and practical considerations [rule out] individually-targeted strategies because policymakers are not allowed to discriminate based on ethnic identity.” However, a “second-best” policy that simply ranks locations based on pooled weighted average estimates of outcomes can lead to worse outcomes for immigrant children (as they are a minority group, and therefore, the weighted average city effect puts, by construction, lower weight on their gains). To minimize the gap between the “first best” and “second best” policies, then, Avivi develops a novel “minimax” model that minimizes the potential harm to any group that might arise due to the inability to provide a targeted policy.

By expanding our understanding of how the long-term effects of location vary across groups, Avivi’s paper contributes to a growing body of evidence on the role of place in determining economic outcomes. The project, which received the 2024 O-Lab and Stone Center Prize for Excellence in Research on Economic Opportunity, also offers new insights into how policymakers can develop sophisticated and equitable policies in settings where the personalized first-best policy is infeasible. In September 2025, Avivi will continue her work as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at University College London, after spending one year as a postdoctoral fellow in the Industrial Relations Section at Princeton University.

Racial discrimination in the New Deal’s Agricultural Adjustment Act

In the early years of the Great Depression, US farmers faced an emergency, as the prices for their goods plummeted due to excess supply. In order to restore farmers’ purchasing power and stabilize prices, President Roosevelt passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933, which, among other things, offered incentives to farmers who did not plant basic crops.

While the AAA was successful in achieving some of its goals, its design and implementation heavily favored white farmers and landowners, while preventing many Black farmers and sharecroppers from collecting benefits they were owed. This has led historians to suggest that discrimination within the program helped drive many Black farmers out of agriculture entirely, although there have been no empirical analyses documenting the impact of the program on Black families’ economic outcomes.

Sheah Deilami-Nugent, a third year student in Berkeley’s Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, is aiming to fill this gap in the literature by investigating how the design of the AAA impacted occupational outcomes and decisions to relocate among Black farmers. Deilami’s interest in the topic was motivated in part by a podcast episode, in which a Black farmer described his struggles in accessing credit. As she dug deeper into this history, Deilami found the AAA repeatedly cited as one of the major sources of discrimination that led to land losses for Black farmers.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act was passed in 1933 to reduce the supply of key crops – corn, cotton, milk, peanuts, rice, tobacco, and wheat – by providing direct payments to farmers who agreed to limit their production of these crops. And while there were no explicitly discriminatory elements in the language of the act itself, its implementation opened two critical doors for discrimination against Black farmers.

First, AAA payments were processed through an existing structure of county-level agricultural extension offices. Extension agents were responsible for both educating farmers on how to claim their benefits and appointing the members of the county committees – consisting of primarily wealthy, white landowners – which processed appeals and complaints from farmers. White extension agents notoriously did not work with Black farmers and sharecroppers – and, while some counties had Black extension agents, the role of Black agents was focused almost entirely on education of Black farmers, and they generally did not have the same power as white agents to appoint committee members. So Black farmers were less likely to be informed about the act and their eligibility, and were less likely to receive a fair hearing when complaints arose.

The process of distributing payments also created incentives for discrimination. Specifically, payments were made exclusively to landowners (often white), who in many cases did not pass on any benefits to sharecroppers and tenant farmers (often Black). Because the complaint process was effectively closed to Black farmers, there was little recourse for Black tenant farmers and sharecroppers to claim the benefits that they were owed.

Deilami hypothesizes that differences in the racial makeup of county-level extension offices may have led to different rates of farmers successfully receiving AAA payments. Specifically, she is exploring whether Black farmers with access to Black extension agents in their counties might have known more about the policy, and had more recourse to receive funds. To investigate this, her project is leveraging agricultural and individual-level census data, AAA spending data, and data on county extension agents and committees. Deilami is still in the process of gathering and analyzing this data – an undertaking which led her to the National Archives in Maryland earlier this year. “I have extension agent data from Louisiana, but I need it for the rest of the Southeast. I might have to go to a few more places to get that data — but it’s amazing to work with archival data, and hold documents that only a few people have held. As a graduate student, you have the privilege to work on these kinds of projects that take a longer amount of time.” Deilami’s goal is to use data on the demographics of extension agents as a source of variation that may be correlated with occupational exit and migration, in addition to long-run outcomes like wealth and income.

While previous work has examined the general effects of the AAA, Deilami’s focus on its racial impacts will contribute important new evidence on the drivers of the Great Migration and how local institutions like the AAA’s county committees can impact long-term outcomes for the people they govern. Deilami also sees her project as well-positioned to catalog the scale of damages done by discriminatory policies, as she notes “This land back in the 1900s that could’ve generated a lot of intergenerational wealth…[that opportunity] is just gone now…the damage has been done.” By contributing to the growing evidence base on the long-term harms of federal discrimination, Deilami’s project provides essential perspective on the importance of equity-oriented policy and implementation.

Evaluating "Imperfectas pero Buenas," Walmart Chile's new initiative combatting food waste

Within the United States and other high income countries, most food waste happens at the household level. In low- and middle-income countries, however, the bulk of food waste occurs at the supplier level, before it ever reaches the consumer. As global food waste accounts for 12% of overall greenhouse gas emissions, the development of scalable strategies for reducing waste along the supply chain is crucial. Can new approaches to food waste simultaneously promote better health outcomes for people with limited resources?

This dual question is the focus of new research led by Daniela Paz Cruzat through the Initiative on Equity in Energy and Environmental Economics, which supports PhD students and undergraduate research apprentices in collaboratively investigating critical questions of energy, environment, and economic opportunity. With the help of two undergraduate mentees, Vanessa Perez and Jessica Yu, Paz Cruzat is working to evaluate “Imperfectas pero Buenas,” or “Imperfect but Good,” an initiative from Walmart Chile aimed at improving customers’ access to nutritional foods while also reducing food waste. By selling produce that does not meet Walmart’s standard shape and color requirements at lower costs, the initiative intends to reduce food waste from agricultural suppliers, who would otherwise waste the 5-15% of their produce considered noncompliant. Selling produce at a reduced price might also reduce barriers to adequate nutrition for low-income consumers, supporting improved health outcomes.

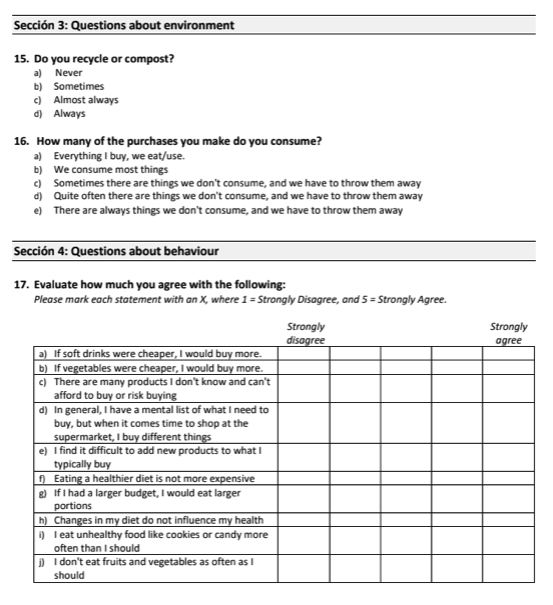

Figure 1: Section 3 of Daniela’s questionnaire for customers asks about environmentalism, while Section 4 features questions eliciting preferences around grocery shopping.

“Imperfect but Good” has rolled out gradually in Latin America: the program was piloted in 7 Chilean grocery stores in September 2022, and Walmart has since expressed intentions to scale the program to additional stores and countries. To empirically measure the program’s effects, Daniela’s will leverage this variation to compare the outcomes of similar consumers and firms who were exposed to the initiative at different points in time. Merging scanner-level product data provided by Walmart Chile (which documents details including product name, brand, price, and discounts) with data on customers enrolled in the Walmart loyalty program will allow Paz and the research team to link purchases to individual characteristics and control for variables including age and gender. Daniela will then supplement data from Walmart with a survey of 2,000 loyalty program members to elucidate the effects of nutritional knowledge, environmentalism, and individual preferences on consumption and program success. At the firm level, Daniela is also working with Walmart to access data from agricultural suppliers that spans firm-level characteristics and transactions, to better understand how the initiative has affected their growth and experience.

Working with a large, private entity like Walmart has presented Daniela with challenges, but also tremendous opportunities for impact at scale. As Walmart had no plans for an impact evaluation of “Imperfect but Good,” Daniela saw an opportunity to offer help – but had to secure buy-in from Walmart leadership. “We started following people on LinkedIn…trying to get our first contact to make other contacts. After a long time, there was one person who clicked with our idea, [and] that was the person who manages the data.” Despite facing initial hurdles related to data access, Daniela is optimistic about the potential impact of the project, due to Walmart’s position as a large, multinational firm, with a growing presence in Latin America. “The size of Walmart…the environmental impact they could have is huge.

Through the Initiative on Equity in Energy and Environmental Economics, Daniela is also guiding her undergraduate mentees as they explore options for graduate school, internships, and careers in energy and environmental research and policy. For Jessica Yu, a senior beginning the graduate school application process, Daniela shared insights on important factors like grades, recommendation letters and exams required. Senior Vanessa Perez, who supported the project by collecting novel data about produce suppliers and translating materials from Spanish to English, entered the mentorship program aspiring to work on sustainability in the private sector, making Daniela’s project a natural fit. While Daniela’s mentees have developed their technical skillsets throughout the project, Paz emphasized the importance of a mentor-mentee relationship that caters to the bigger picture. “I feel that undergraduates are a bit alone…with decisions, where to work, how to ask people for a meeting, what to ask in the meeting, how to write an email…For one of our mentees, it was her first experience coding with real data. That’s great, but it’s also the people you know, the contacts, the networking…that [support] can be extremely valuable.”

Property taxes, wealth inequality, and economic activity: lessons from São Paulo, Brazil

As wealth inequality continues to grow around the world, and as economic activity is increasingly geographically concentrated, there are wide-ranging debates in the economic literature about the role tax policy should play in promoting more equitable distribution of wealth and opportunity. In many rich countries, property taxes represent one of the most prominent tools for raising revenue and incentivizing economic activity in one location versus another. However, since property taxes are rarely used in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there is a gap in our understanding of how effectively they might work to affect disparities and economic activity in different contexts.

Brazil offers a unique case study for examining the role property taxes can play in reducing both geographic and racial wealth disparities in an LMIC context. With a robust data infrastructure for researchers to draw upon, and a recent tax reform aimed at creating more equitable distribution of economic activity, the country presents an opportunity to deepen our understanding of how individuals and firms respond to taxation and how taxation on high-value property can act as a tool for redirecting economic activity and promoting greater racial equity. Supported by O-Lab’s Place-Based Policy Initiative, Javier Feinmann, a PhD candidate in Economics, and his collaborators Roberto Hsu Rocha, Davi Moura, and Thiago Scott, are investigating these questions, drawing upon a rich dataset from the city of São Paulo.

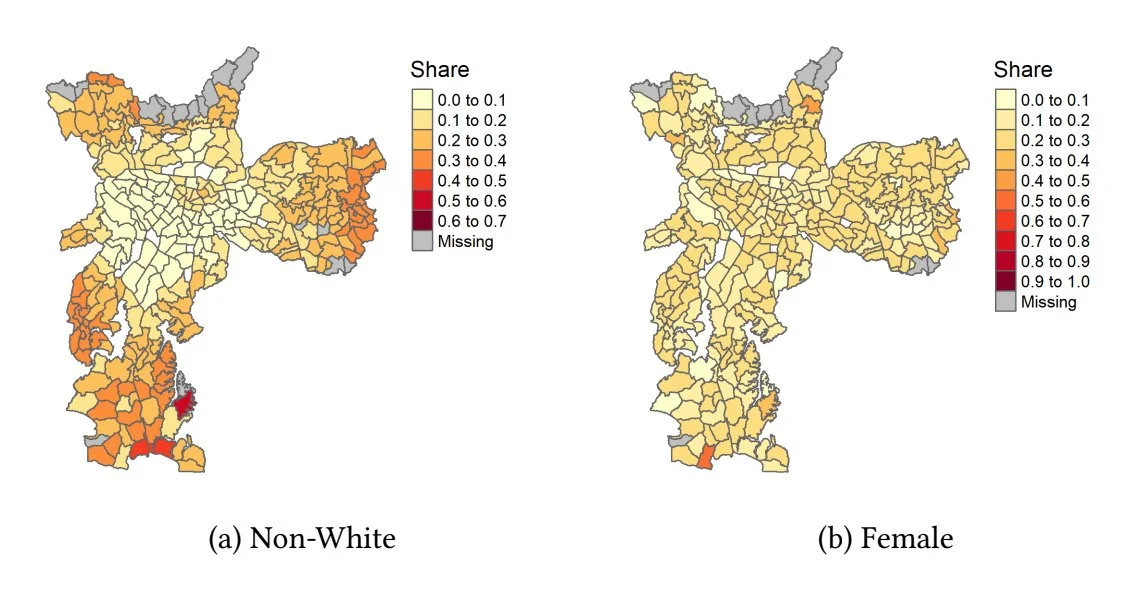

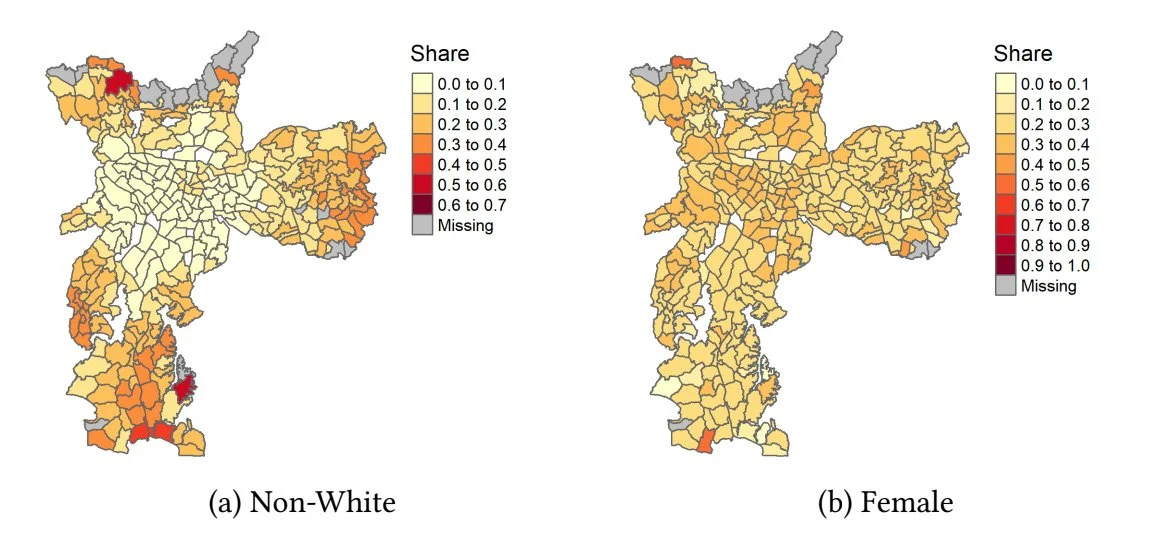

In the first stage of his research, Feinmann and his team are working to understand existing racial and gender disparities in wealth and property ownership in São Paulo. The researchers’ work is supported by a wealth of administrative data that allows him to create highly granular maps of property ownership and property tax rates. The project’s starting point is a database on annual property assessments in São Paulo. Using location-specific property identifiers, the team can spatially plot property values and tax rates throughout the city. Then, using a separate dataset which includes demographic information, they can link these properties to their owners, allowing race and gender identifiers to be incorporated into the map.

Figure 1: Geographical Segregation of São Paulo Property Ownership by Fiscal Zone

Figure 2: Geographical Segregation of São Paulo Wealth by Fiscal Zone

In this descriptive stage of his project, Javier and the team have confirmed disparities in property ownership for women and minority groups. In particular, the researchers find that across all property types and regions of São Paulo, women own fewer properties than men. The team has also found substantial racial disparities in property ownership; however, these are more variable across different regions of the city – likely resulting from existing regional segregation. In general, these gaps in gender and racial ownership are more pronounced among high-value properties.

In the next stage of his project, Feinmann will take a few extra steps to paint a more detailed picture of the distribution of property wealth and tax burdens in São Paulo. Specifically, since the state of São Paulo publicizes the registration of all businesses, Javier and coauthors are able to track the ultimate owners of registered firms that own property in São Paulo, including owner demographics. Then, the property wealth owned by firms can be proportionally assigned to ultimate owners. This novel approach provides a more comprehensive picture of who owns what in São Paulo. By accounting for individuals who own real estate through firms, this project also makes an important contribution to contemporary conversations by economists including Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez on how to accurately measure wealth held by the top percentiles.

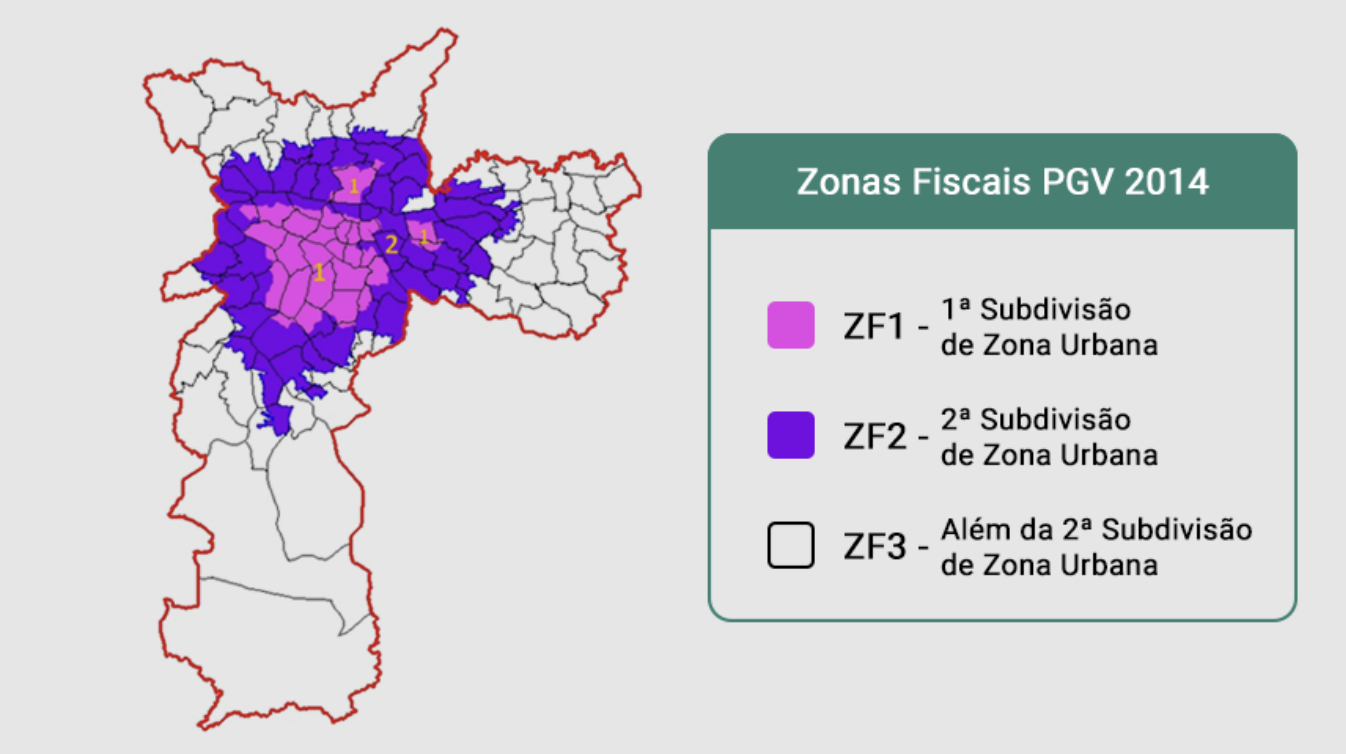

Figure 3: New fiscal zones instated by the 2014 tax reform.

Going forward, the researchers will use their findings as a basis for an analysis of how a major 2014 property tax reform in São Paulo affected economic activity and firm behavior in the city. The law in question divided São Paulo into three separate fiscal zones, and revised the property tax assessment formula to increase taxes on properties closest to the city’s wealthy central district. The intention of this change was to more equitably distribute property tax burdens in São Paulo – was the policy successful? What were the policy’s consequences for the location of economic activity – did it incentivize firm creation in less affluent, low-tax areas, or purely encourage existing firms to relocate? Upcoming stages of this project will explore these questions, and produce important new evidence on how regionally-targeted tax policies can influence racial and gender disparities in property ownership and wealth.

How does increased minority enfranchisement impact public finance, preferences for public goods, and government fragmentation?

In 2013, the US Supreme Court issued a controversial ruling in the case of Shelby County v Holder, severely limiting the power of the federal government to enforce provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA). Before the ruling, changes to voting regulations by certain state and local governments were required to be “pre-cleared,” or deemed nondiscriminatory, before they were allowed to go into effect; after the ruling, it became the responsibility of disenfranchised voters to advocate for themselves and demonstrate that changes to voting laws were discriminatory.

This landmark ruling inspired a series of new studies examining the historical impacts of the VRA, in an effort to better understand its consequences and forecast the potential impacts of the Shelby decision. Raheem Chaudhry, a PhD candidate at the Goldman School of Public Policy, is leading one such study through his participation in the O-Lab’s Initiative on Racial Equity in the Labor Market.

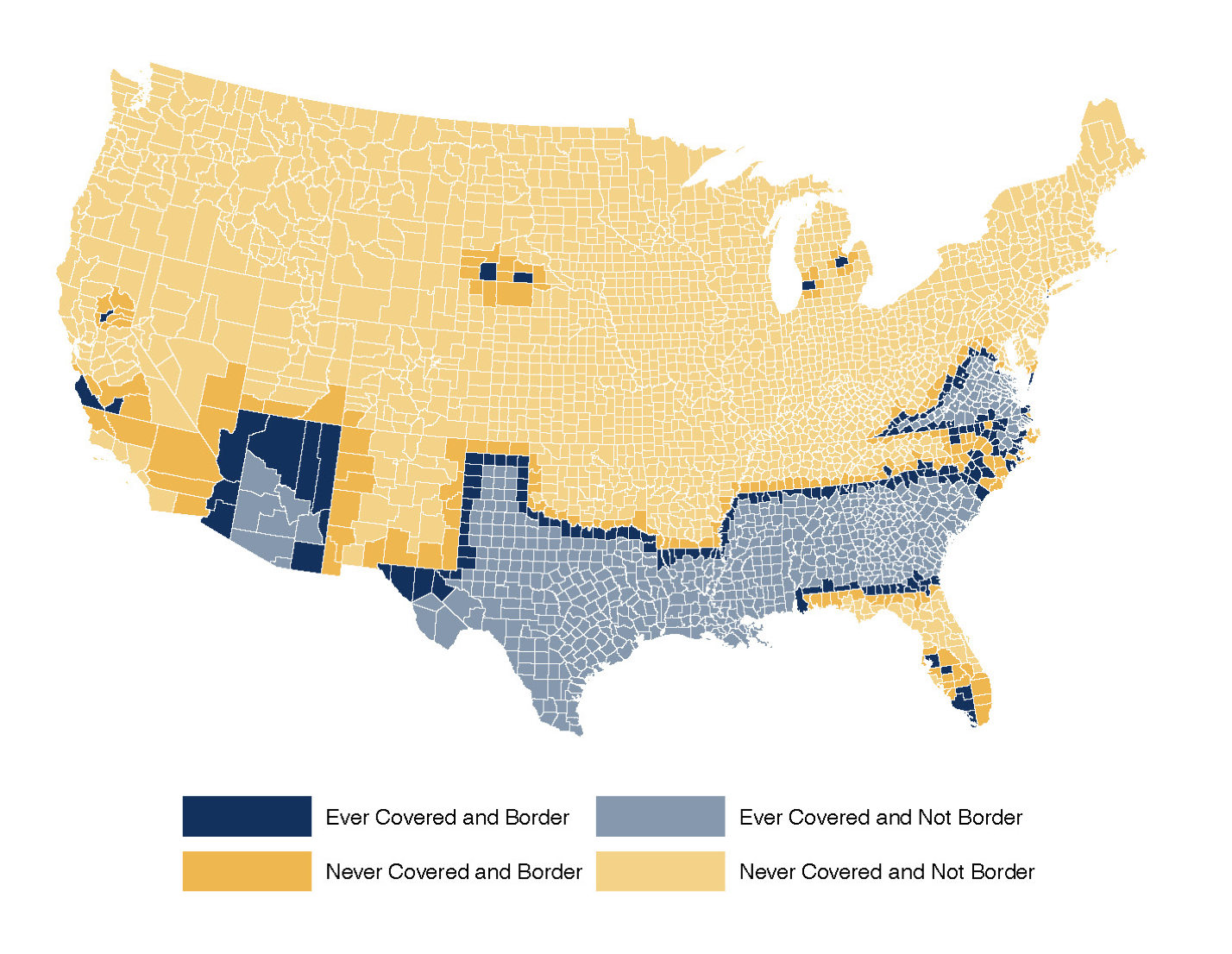

Raheem’s research focuses on how the VRA impacted local and state revenues, as well as municipal spending on a variety of services and programs – hypothesizing that higher turnout among Black voters would lead to increased spending on public goods. Raheem used data from the Census of Governments, a survey conducted every five years, to get a detailed picture of government spending at all levels, including cities, counties, and special districts. He then compared jurisdictions covered by special provisions of the VRA that applied to only especially discriminatory districts to similar, geographically-adjoined districts, in order to isolate the impact of these parts of the Act. Subsequently, he was able to compare differences in spending in districts impacted to those unaffected.

Initially, Raheem expected to find increases in public spending in those jurisdictions with substantial Black populations that were identified by the VRA as particularly discriminatory (those required to pre-clear any future changes to voting laws). In actuality, he found that counties with larger non-white population shares demonstrated relative declines in government revenues and expenditures — but why? Raheem’s working theory, informed in part by existing literature, sees these changes as a response to increased integration. By ruling out tax base changes as the cause of declining public spending — there were no significant changes in home values or incomes during the period of study — Chaudhry’s work offers a compelling narrative that voters in these districts were less inclined to finance increasingly integrated public resources. Further evidence in support of this theory can be seen in decreased levels of public school enrollment, particularly among white students, from 1968 to 1972 – which suggests that families turned to private school in response to increased integration. Raheem also found relative increases in government fragmentation amongst counties targeted by special provisions of the VRA with larger non-white populations. This finding follows existing literature, and suggests a mechanism by which increasingly integrated counties sought to maintain local control over public finances.

Raheem’s project complements a growing body of work among economists that shows the limits to migration as a tool for surmounting racial income inequality. His work adds an important focus, however, on the role of political power in the success or failure of policies promoting access to resources such as education, transportation, and more. “I think the way that people traditionally think about this is, ‘How do we move kids to high opportunity areas?’ But you can also think about, ‘How do you transform the places kids already live?’ And one way you can do that is through the political process.” While Chaudhry’s project does not find an explicit positive impact of the VRA on local public spending, it nevertheless has important lessons for policymakers. In particular, his work shows the powerful way in which racial backlash can undermine efforts to more equitably allocate public resources.

How do major flooding events impact women’s labor force participation in India?

As climate change increases the intensity of natural disasters, India’s monsoon season and resulting flooding increasingly threaten women’s autonomy. Globally, researchers are concerned that climate events are reversing progress made in women’s labor force participation, especially in low-income or rural areas. Elena Stacy, doctoral candidate in Berkeley’s Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ARE) and fellow through the O-Lab and Energy Institute’s Initiative on Equity in Energy and Environmental Economics, investigates this dynamic in detail in her project: “The Impact of Floods on Women’s Empowerment and Female Labor Force Participation in Rural India in the Age of Climate Change.”

Before beginning her PhD at UC Berkeley, Elena spent time as a Pre-Doctoral Research Assistant with Yale’s Economic Growth Center. There, she worked on a project designed to improve the cost and time-effectiveness of time use surveys, a type of survey module which measures how individuals allocate time towards different activities in a 24-hour period. Elena worked with Rohini Pande in Patna, Bihar, during the summer — India’s rainy season — and was often ankle-deep in water on her walk to work. It was the combination of these experiences that led Elena to consider using time-use data to better understand how women are impacted by climate disasters in India.

Elena’s project stands to explore the relationship between labor outcomes and climate impacts in a rural setting with an emphasis on gender disparities, filling an important research gap: while researchers have studied why women’s participation in the workforce is declining in India, and multiple studies have demonstrated how labor force participation advances women’s autonomy, few studies focus on how climate change complicates this dynamic. Elena’s paper contributes to this literature by leveraging time use data, which provides new insight into the drivers of low labor force participation among women. “If women are shifting away from labor, what is their time used on instead?”

To understand how women’s labor force participation is impacted by flooding, Elena cross-references time use data with geospatial data from the NASA MODIS satellite dataset. After converting geospatial images to usable data, she can estimate the severity and timing of flooding in different districts. Because the time use data is collected at different points in the year, it’s then possible to measure how women’s time use changes before and after a major flood event.

Eman Nazir, Undergraduate Research Apprentice

Hayley Lai, Undergraduate Research Apprentice

Through the 2022-2023 academic year, Elena has been conducting this work as part of O-Lab and the Energy Institute’s Initiative on Equity in Energy and Environmental Economics, which pairs graduate student fellows with undergraduate students, who benefit from research experience and graduate student mentorship. During her time as an undergraduate student at Berkeley, Elena spent time as an undergraduate research assistant herself, influencing her participation in the initiative: “My personal experience as an undergrad has definitely played a role in my own desire to be a graduate student mentor, and has also informed my approach in it.” Elena’s undergraduate mentees, Eman Nazir and Hayley Lai, have previous experience advocating for environmental justice and women’s empowerment; Elena described how it was important for her to steward their curiosity in her research questions, and provide plenty of country context, to lay a foundation for their data analysis tasks. Since beginning their partnership in Fall 2022, Eman and Hayley have built on their existing experience with R to tackle more advanced data cleaning tasks, and gained experience working with geospatial data. “They’ve put in a lot of work in terms of understanding the project, advancing their programming skills and conducting research,” says Elena. “I’m lucky to have two great, undergrad women in Econ on my mentee team.”

While Elena is still in the early stages of her project, she’s hopeful that her research will inform meaningful policy impact and spur future research on the intersection of gender and climate change in India. In the short term, as Elena cleans, links, and processes novel data, she intends to share it online, alongside her code, in order to make it more approachable for other researchers to examine the impacts of flooding. In the future, if her work does find that floods and severe climate events are disproportionately shifting women away from labor, she hopes that policymakers will make efforts to alleviate these disparities — for example, by specifically targeting women through the state’s existing government labor program, NREGA, or providing alternative childcare options in the event of school closures.

Understanding the Distributional Impact of New Electricity Technologies in Senegal

How do different electricity technologies impact the way that we use energy — and how should technological roll-outs be targeted in order to achieve efficiency gains to both customers and utilities? Abdoulaye Cissé, a Ph.D. candidate in Agricultural and Resource Economics, has spent his time as a Fellow through O-Lab and Haas Energy Institute’s Initiative on Equity in Energy and Environmental Economics asking these questions.

Cissé’s research aims to better understand the energy and electricity value chain in Senegal, where he was born. Cissé grew up hearing conversations about electricity, and his project was heavily inspired by energy issues his family and community faced at home. "There’s a lot of discussion around electricity that I wound up hearing, a lot of issues I grew up experiencing. If you look at the last two changes of power in Senegal, many would argue that, at least partially, they had to do with electricity shortages being quite significant,” he said.

After reading a news article in 2020 citing transparency issues around electricity rates and payment structures, Cissé approached Senegal’s state electricity utility, Société Nationale d’Electricité du Senegal — or SENELEC — in the midst of a new technology rollout. With the provision of smart and prepaid meters, customers would now be able to see their real-time energy consumption and price, with the goal of encouraging cost-saving and energy conservation. Meters also report back to the utility company, enabling informed distribution decisions and limiting losses. Cissé is investigating how the roll-out might impact consumers differently. He proposed a research project to examine the project’s welfare implications in detail; SENELEC was responsive and agreed to support his research. For SENELEC, an analysis of the impact of new technologies on electricity use is crucial to the reduction of “technical losses” (for example, electricity lost through transmission, distribution, and measurement systems), as well as non-technical losses (such as unpaid bills) at points of consumption.

To study the impacts of the new metering technologies, Cissé is examining billing and payment records, provided by the state energy utility, to understand how much consumers pay for electricity and whether bills are paid on time. Payment data is then cross-referenced with electricity consumption data, building a consumption and purchase history for 1.7 million customers over ten years. Each piece of billing data is associated with an address, allowing Cissé to cross-reference consumer data with regional and local satellite data estimating different economic variables. Altogether, these data allow Cissé to analyze a variety of predictors for Senegalese electricity consumption and payment, isolating the impact of new technologies on energy use. In particular, the data will help Cissé learn whether - and how - consumer decisions may be changing as a result of the new technologies.

Cissé’s project provides crucial insights on the general economic impact of electrification as well as potential distributional consequences of the rollout of the technology, and the analysis of SENELEC’s data alongside satellite data will allow him to see how the economic gains from electrification may accrue differently across regions and income groups. This is especially important in Senegal, where Independent Power Producers (IPPs) – private companies that generate electricity for sale to SENELEC – are often located in rural areas, yet produce power for urban centers. The costs of power generation in these rural areas can be substantial, and include land clearance, noise pollution, emissions from non-renewable power generation, and spillover effects of power plants on local ecosystems. These impacts burden rural populations, while the benefits of electricity generated accrue more to urban residential and commercial clients. Accordingly, the design of power generation to increase electricity access has distributional impacts that warrant further analysis.

Ella Tyler, Undergraduate Research Apprentice

Analyzing ten years of electricity bills and purchases, across an entire country, is no small feat, and Abdou has benefitted in his work from the support of undergraduate research assistants he is mentoring through the Initiative on Equity in Energy and Environmental Economics. As part of this initiative, Abdou has mentored 4 students, providing research training experience and guidance on careers in environmental policy and research. Ella Tyler, for example, worked with Abdou through the 2021 - 2022 academic year; she brought a strong data science background to the project and used her Python skills to help Abdou with data analysis. At the same time, he offered her training in research methods and helped her set up a job as a Research Assistant in Sierra Leone.

As he enters his fourth year in the Ph.D. program, Cissé is nearing the final stages of his data collection work: combining geocoordinate data from SENELEC with remote sensing data and identifying the economic metrics that make the most sense to consider in his analysis. With funding from O-Lab and the Energy Institute, Cissé also hopes to collect primary data on a subset of households next spring, in order to get to know clients beyond their consumption data and consider more predictors of behavior around electricity consumption and payment.

Cissé is regularly in touch with SENELEC, and hopes to return to the utility with policy recommendations related to the impact of meters on energy demand, how to target roll-outs to different types of customers, and the impact of the meters on the economic conditions of residential and commercial customers. He is optimistic about the potential for his research to inform policy on how to best strategize these investments.

How Place-Based Climate Policy Can Reduce Climate Emissions

How does a community’s built environment and access to public goods impact their carbon emissions? How does income inequality impact peoples’ options for reducing carbon emissions? Fifth-year PhD candidate and O-Lab fellow Eva Lyubich is exploring these questions in an ongoing set of projects focused on how place-based climate strategies might help curb climate emissions. Eva’s research interests lie at the intersection of climate policy, inequality, and public goods provisions, and she is particularly focused on finding viable solutions to mitigate the climate crisis.

In ongoing work, Eva is studying whether place-based climate policies - climate policies focused on local investments in climate mitigation solutions - would be more effective than carbon taxes at reducing carbon emissions. Economists typically suggest that carbon taxes force people to privately account for the harm they contribute to globally. However, people’s ability to substitute away from dirty energy consumption is highly dependent on alternatives available to them on a local level. “If certain public goods investments have the capacity to reduce carbon emissions for many people all at once, then it may be more efficient to make investments in public goods rather than relying on individuals to make private investments on their own,” she said. For example, policies that change the built environment of a community, such as making it more walkable, bikeable, or investing in public transit reduce carbon emissions while positively benefiting a community by increasing the available transportation options.

Eva’s motivation for this paper came from “the idea that individuals are constrained by the choices they can make and could therefore be limited in their ability to reduce their individual carbon footprints.” A few of the questions behind this research agenda include: How do characteristics of places constrain our ability to reduce emissions? Would people change their behaviors if we changed the characteristics of a place? Do people drive because they don’t have access to high quality public transit or do they like driving and will they drive everywhere regardless of if they have access to a public transit system? Eva is trying to estimate what share of geographic variation in carbon emissions is driven by characteristics and policies governing the places people live in versus differences in people’s preferences.

“Individuals are constrained by the choices they can make and could therefore be limited in their ability to reduce their individual carbon footprints.

In this project, Eva estimates what share of emissions are place-based using what is known as a mover design, in which she studies how people’s emissions change as they move to different places. She hopes to use these estimates to inform what type of investments and what geographic locations have the highest benefit to cost ratio in reducing overall emissions. According to Eva, “this research has the potential to help local, state, and federal governments determine where we should be investing to make the highest emissions reductions.” An example of an existing program that is making place-based climate investments is the California Climate Investments initiative, which uses cap-and-trade revenues to fund community-based projects for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in disadvantaged communities.

“This research has the potential to help local, state, and federal governments determine where we should be investing to make the highest emissions reductions.

More broadly, Eva plans to study the consequences of income inequality on our collective ability to address the climate crisis. The availability of a community’s options to reduce their carbon footprint is highly impacted by the distribution of public goods, which is largely dependent on the income distributions of a community. Income inequality and mitigating the climate crisis go hand in hand. “In a future project, I hope to study how the distributions of public goods and income inequality intersect with climate policy effectiveness. Does income inequality across communities prevent climate policy from being successful?” Eva’s research projects have great potential to influence social policies, climate policies, and secure our planet’s future.

Examining Incomplete Take-Up of Safety Net Programs

Not all individuals enroll in the public programs and claim the assistance for which they’re eligible. Why? Do families not know programs exist or not know they’re eligible? Is it too time-consuming or complicated to enroll or stay enrolled? Or perhaps receiving this type of assistance is too stigmatized? Does the importance of these explanations vary by program and across different communities? And what can policymakers do to promote take-up of these critical programs?

These questions have been the focus of multiple research projects pursued by Matt Unrath, a fourth-year PhD candidate in public policy. As a Research Fellow at the California Policy Lab (CPL), Unrath has had the opportunity to study these questions and experimentally test possible solutions at a large scale. Through CPL’s partnership with the California Department for Social Services and the Franchise Tax Board, he and his colleagues spent years building an administrative dataset linking state welfare enrollment records to state-level tax records. This dataset has proved a critical tool, allowing CPL researchers to examine participation in California’s means-tested welfare programs and eligibility like never before.

For example, Unrath and his coauthors ran a number of randomized controlled trials to test the impact of providing information about the federal and state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) on take-up of the program among eligible Californians. The team sent this information via hundreds of thousands of letters and text messages to eligible households to see what kind of information and what type of nudge would cause people to file their taxes and claim the benefit. Using matching tax records data, the researchers were able to determine whether or not the people who received information were more likely to claim the EITC.

The result? “None of our interventions worked,” Matt said. “We can rule out that we nudged anyone to file by just providing them this information.” These findings indicate that there is a limit to nudge-style outreach programs and what just providing more information can accomplish in this context. Additionally, Matt and his coauthors conclude that information is not the barrier to increased take-up in this instance. “If we really want to increase take-up of programs that are delivered through the tax system, we should think about how to make tax filing a lot easier,” Unrath concludes.

His team is now working to measure take-up of the state-level EITC supplement in California. “We really don’t know how many people claim the California EITC supplement because all of our measures of take-up are done nationally,” Matt explains. By aligning Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), or food stamps, household data and tax data in California, “Could we create a model for states across the country to use their state administrative data to identify these likely eligible people and measure take-up of their own state-level EITC programs?”

In forthcoming work, Unrath also examines the effect of administrative burdens on enrollment in CalFresh, the SNAP program in California. Using fifteen years of administrative data for the country’s largest SNAP program, he documents a significant drop off in enrollment every six months, when participants are required to recertify their income eligibility in order to maintain benefits. Linking CalFresh data to state earnings records, he finds that, “The great majority of people appear to be income-eligible even when they exit the program.”

These projects point to the role that administrative procedures play in affecting program participation. Unrath points out that these processes are an inevitable feature of our choice to means-test safety net programs; the government needs to identify who is eligible, and that will impose some costs on applicants and enrollees. Some economists have posited that making these processes even more burdensome might discourage those on the margin of eligibility from enrolling, enabling more assistance to be targeted to individuals and families that are the least well-off. But do administrative burdens actually operate in this way?

“People are aware that making processes harder deters participation, but what we don’t know as well empirically is who these processes are more likely to deter from participating. The concern is that we are not doing the right thing, and we are actually deterring folks who are more disadvantaged,” Unrath explains.

Contrary to theory, “You can imagine an alternative framework in which these burdens deter the folks who are the most disadvantaged, who face the most burdens in their daily lives, and who are least able to handle all the paperwork they need to file in order to apply for and stay enrolled in a program,” he adds. The database that CPL have constructed should enable Unrath and his colleagues to evaluate whether these administrative processes have this effect..

Unrath’s research is highly relevant for policymakers, many of whom are very concerned about incomplete take-up of the EITC in their states. In the short term, he points out, “The pandemic shines a spotlight on how to think about the administrative process of getting payments to people quickly and efficiently.” Longer-term, he adds, “There’s a lot of momentum in California to try to begin to use the matched dataset programmatically on an ongoing basis,” following CPL’s novel efforts in this area.

Examining the Role of Housing Regulations in Exacerbating Wealth Inequality

The stark inequalities that have divided American society over the past three decades don’t just appear in people’s paychecks. They also increasingly determine where Americans live, how much preparation their children receive for the future, and whether workers can count on predictable and steady work from one week to the next.

Those are the sorts of diverse forms of social inequality that Joe LaBriola, a sixth-year sociology Ph.D. candidate, has built his academic career researching. He’s explored, for example, the role of worker power in reducing inequality in work hour instability. That paper, written with O-Lab affiliate Daniel Schneider, won LaBriola the 2018 IPUMS USA research award for best graduate student paper.

“The thing that jumped out to us is that right after the Great Recession, work hour volatility spiked for workers who were less educated and making the least amount of money,” LaBriola said. “Next we want to think about what we think is causing work hour volatility.”

LaBriola has been a prolific researcher, with five peer-reviewed publications and three chapters looking at subjects such as the effects of post-prison employment quality on recidivism, risk-taking at U.S. commercial banks, and how class gaps in parental investment in children change during the summer. His research is motivated by a recognition that the well-off enjoy more advantages at every stage of life, and that those at the bottom end of the workforce are too-often denied the security and benefits of full-time and predictable employment.

Another of LaBriola’s ongoing projects focused on how home ownership - and the attempts of some homeowners to restrict the development of new housing - has exacerbated wealth inequality. He points to research showing how the housing market increasingly shuts out low-income people who are hoping to build wealth through ownership. The “wealth gaps” that then arise can be just as consequential as income gaps, and only exacerbate and compound inequality over generations.

“If we build more housing supply, this could be something that will even out the playing field in terms of household wealth allotment,” LaBriola said. “Wealth inequality is not something that’s talked about as much as income equality, but it’s extremely important because wealth determines the amount of resources you have to move around in the world.”

For his research on housing development, he is merging national data on residential building permits going back to 1980 with data on household finances. He is also investigating the relationship between lawsuits over residential land use policy and housing development.

“I’m interested in whether homeowner opposition to new housing is a form of social closure,” LaBriola said. “Basically, people who already have a house they like - and who like the neighborhood they live in and don’t want to change - they might gain wealth by keeping it this way while everyone else suffers.”

Applying New Data to Understand Gender Disparities in the Workplace

Gender inequality among top employee ranks has proved stubbornly persistent over the years, with management positions still dominated by men in much of the corporate world.

Labor economists have long asked whether that disparity results from women not applying for higher positions or from active discrimination against women applicants. O-Lab Graduate Fellow Ingrid Haegele is helping to answer that question with the use of a large new dataset that helps her study patterns of application, hiring, and promotion within a single large multinational company.

With this peek inside what she calls the corporate “black box,” Haegele has discovered that, at the company she analyzed, much of the lack of gender equity in management resulted from the fact that many women weren’t applying for their first management-level positions, even when they were well-qualified for the job. This disparity in the promotion chain then has long lasting consequences for employees’ careers, such as reduced lifetime earnings and additional gender disparities in upper management.

“Women and men make different choices when it comes to internal applications,” Haegele said about her findings. “Women apply more for lateral positions and they are less likely to apply for higher ranking positions than men. Since these differences in applications have large effects on employees’ promotion outcomes, I decided to focus on understanding what leads to these choices”

Haegele, a German native, is sifting through data that previously had not been available to economists, such as internal application and hiring data. With those data, she is able to follow the career paths of thousands of employees and calculate the probability that they’ll be promoted during their time at the organization.

Haegele then built upon this dataset by surveying 17,000 employees about their choices to apply or not apply for more senior positions, and what they thought about their chances of advancing. The responses – she received a nearly 50% response rate to the survey - revealed that men and women react to job ads differently. Women have a strong preference for jobs that offer a high degree of flexibility, for example, suggesting that companies seeking to diversify their management staff may need to tailor how those positions are designed in order to make them more appealing to women.

In addition to the broader insights this work is generating, it is also providing concrete opportunities for Haegele’s corporate research partner to implement and test new HR policies in response to her findings. “We’re trying to see if, by providing tailored career assistance, we can support women’s career development,” Haegele said. And as part of her next phase of research, she will be running text analyses on 16,000 job ads at the company to help determine whether men and women are motivated to apply for different sorts of job openings. That analysis will help her identify language that may potentially appeal differently to men and women applicants.

Working with Economics professor Patrick Kline, Haegele said she was regularly encouraged to ask big questions in her research. “There are still a lot of things about organizations, career progression and management practices that we as economists don’t know,” Haegele said. “I am currently working on a separate project...that tries to trace out how career paths change over the employee life-cycle and what that teaches us about an aging workforce. I am very enthusiastic about conducting research on how organizations are designed and how this impacts labor market outcomes and I am looking forward to many more projects like this.”