As wealth inequality continues to grow around the world, and as economic activity is increasingly geographically concentrated, there are wide-ranging debates in the economic literature about the role tax policy should play in promoting more equitable distribution of wealth and opportunity. In many rich countries, property taxes represent one of the most prominent tools for raising revenue and incentivizing economic activity in one location versus another. However, since property taxes are rarely used in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there is a gap in our understanding of how effectively they might work to affect disparities and economic activity in different contexts.

Brazil offers a unique case study for examining the role property taxes can play in reducing both geographic and racial wealth disparities in an LMIC context. With a robust data infrastructure for researchers to draw upon, and a recent tax reform aimed at creating more equitable distribution of economic activity, the country presents an opportunity to deepen our understanding of how individuals and firms respond to taxation and how taxation on high-value property can act as a tool for redirecting economic activity and promoting greater racial equity. Supported by O-Lab’s Place-Based Policy Initiative, Javier Feinmann, a PhD candidate in Economics, and his collaborators Roberto Hsu Rocha, Davi Moura, and Thiago Scott, are investigating these questions, drawing upon a rich dataset from the city of São Paulo.

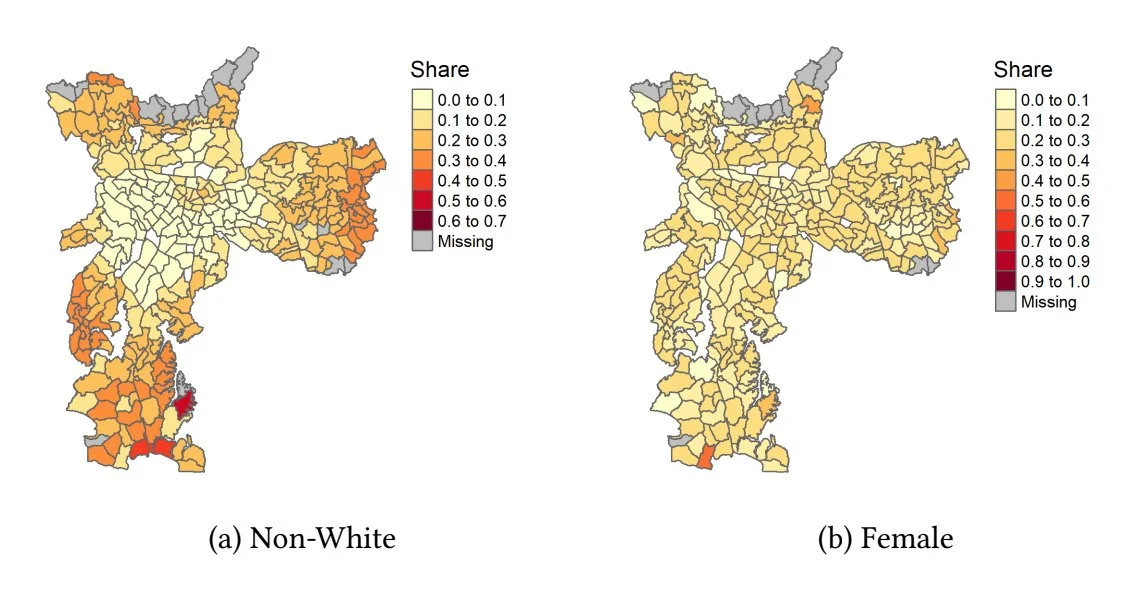

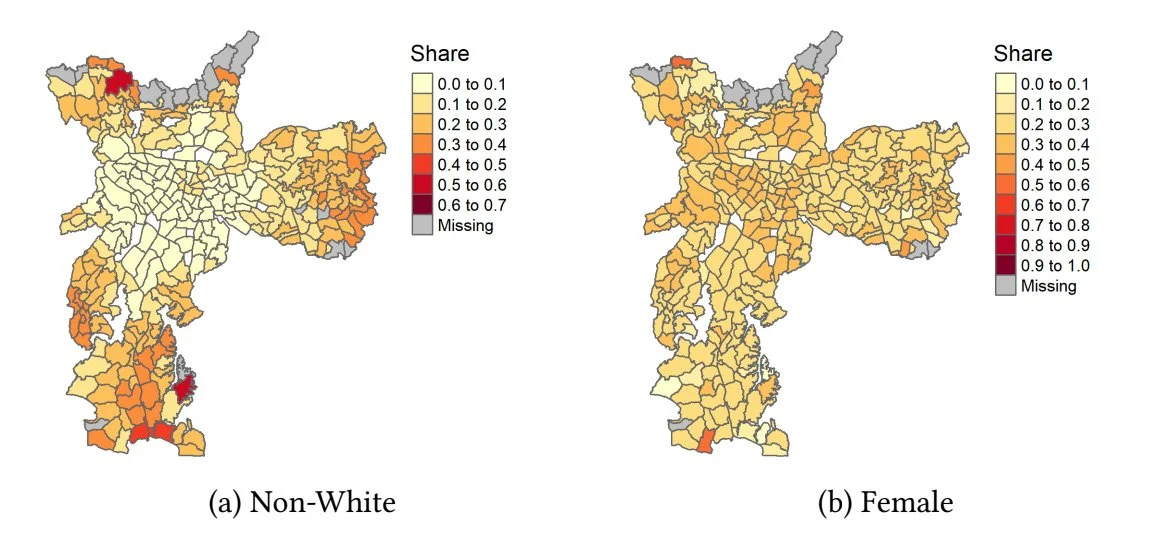

In the first stage of his research, Feinmann and his team are working to understand existing racial and gender disparities in wealth and property ownership in São Paulo. The researchers’ work is supported by a wealth of administrative data that allows him to create highly granular maps of property ownership and property tax rates. The project’s starting point is a database on annual property assessments in São Paulo. Using location-specific property identifiers, the team can spatially plot property values and tax rates throughout the city. Then, using a separate dataset which includes demographic information, they can link these properties to their owners, allowing race and gender identifiers to be incorporated into the map.

Figure 1: Geographical Segregation of São Paulo Property Ownership by Fiscal Zone

Figure 2: Geographical Segregation of São Paulo Wealth by Fiscal Zone

In this descriptive stage of his project, Javier and the team have confirmed disparities in property ownership for women and minority groups. In particular, the researchers find that across all property types and regions of São Paulo, women own fewer properties than men. The team has also found substantial racial disparities in property ownership; however, these are more variable across different regions of the city – likely resulting from existing regional segregation. In general, these gaps in gender and racial ownership are more pronounced among high-value properties.

In the next stage of his project, Feinmann will take a few extra steps to paint a more detailed picture of the distribution of property wealth and tax burdens in São Paulo. Specifically, since the state of São Paulo publicizes the registration of all businesses, Javier and coauthors are able to track the ultimate owners of registered firms that own property in São Paulo, including owner demographics. Then, the property wealth owned by firms can be proportionally assigned to ultimate owners. This novel approach provides a more comprehensive picture of who owns what in São Paulo. By accounting for individuals who own real estate through firms, this project also makes an important contribution to contemporary conversations by economists including Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez on how to accurately measure wealth held by the top percentiles.

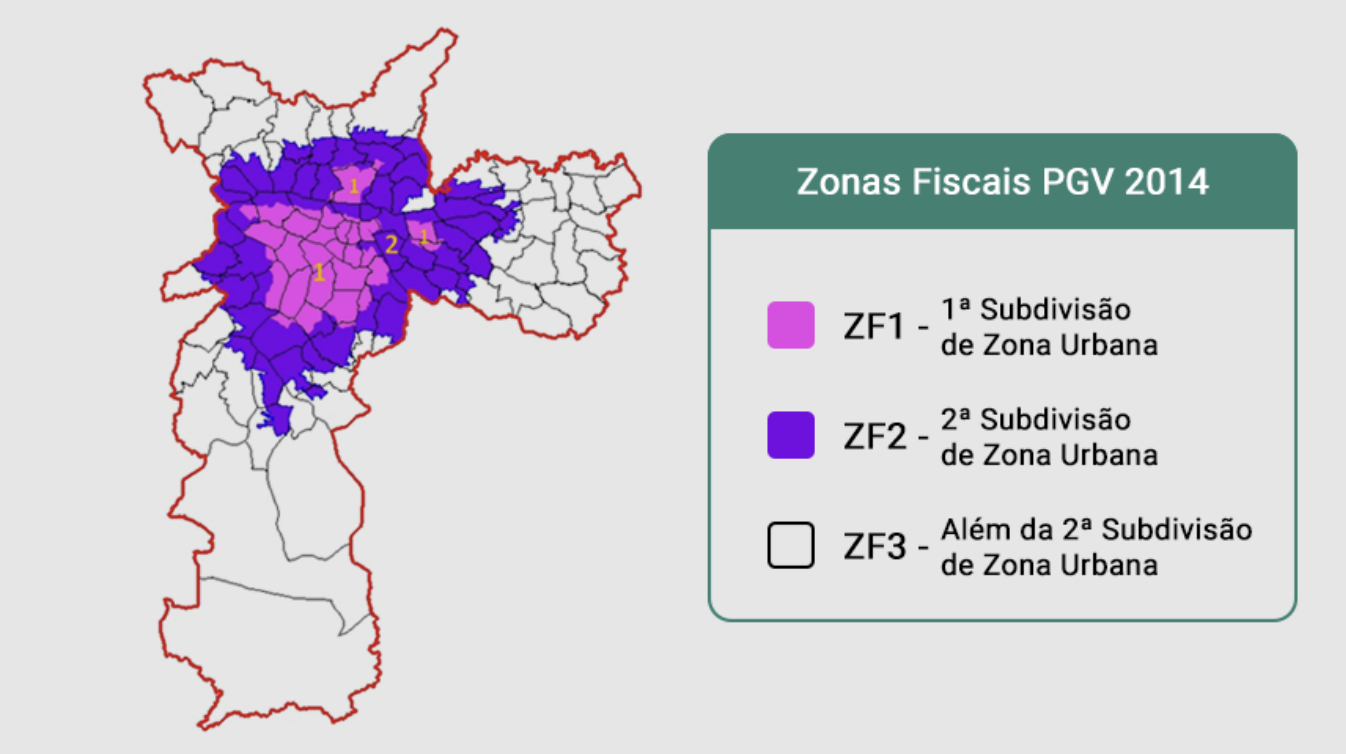

Figure 3: New fiscal zones instated by the 2014 tax reform.

Going forward, the researchers will use their findings as a basis for an analysis of how a major 2014 property tax reform in São Paulo affected economic activity and firm behavior in the city. The law in question divided São Paulo into three separate fiscal zones, and revised the property tax assessment formula to increase taxes on properties closest to the city’s wealthy central district. The intention of this change was to more equitably distribute property tax burdens in São Paulo – was the policy successful? What were the policy’s consequences for the location of economic activity – did it incentivize firm creation in less affluent, low-tax areas, or purely encourage existing firms to relocate? Upcoming stages of this project will explore these questions, and produce important new evidence on how regionally-targeted tax policies can influence racial and gender disparities in property ownership and wealth.