Assistant Professor Cailin Slattery joined the faculty of Haas School of Business in the Fall of 2023. Her work focuses on the relationship between firms and local governments, and on the role state and local incentives play in driving local economic development.

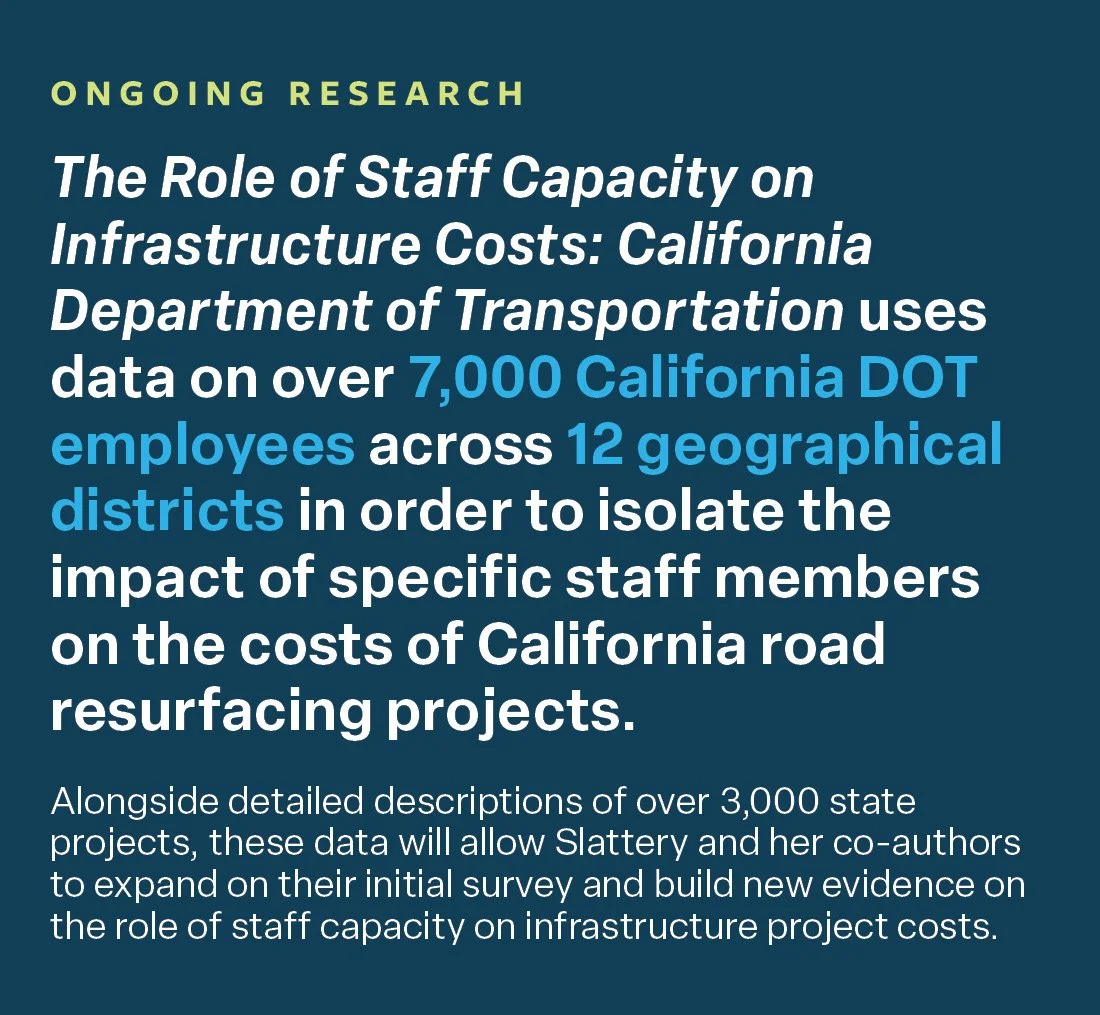

Slattery is also one of the leaders of O-Lab’s new initiative on US Transportation & Infrastructure Development, which is building a new body of research on what kinds of policies and strategies governments can deploy in efficiently and equitably bringing large-scale infrastructure and transportation projects to fruition. As part of this initiative, Slattery is leading new work on the drivers of transportation costs in the United States. In particular, she and her co-authors are examining how much of the cost of road maintenance and resurfacing costs are influenced by the competence of the managing agency staff. The research builds on work she conducted with co-authors Zach Liscow and Will Nober to survey procurement practices across all 50 states to understand what those working on procurement and maintenance on the ground think about what’s driving the costs, as well as what the actual variation looks like across states.

We recently sat down with Cailin to learn more about her research and the potential lessons for policymakers that could result from her ongoing work into the drivers of high costs in US road maintenance and resurfacing projects.

Cailin, your work focuses on identifying what’s driving up costs in US road projects - before we get into it, it would be great if you could provide some background on what we know more generally about the costs associated with infrastructure development in the United States. How does the United States compare to other high-income countries?

You're starting off with a hard question – we don't know a ton. There's really good research on transit costs across countries – subways and light rails – but not on resurfacing and road building, which my paper looks at. The US does look like an outlier, in terms of how much it costs to build a mile of subway in New York, versus in Paris or in Rome.

We focus on roads because it’s the bulk of the work that state DOTs are doing – every state is maintaining their roads and their bridges. But not many states at this point are building new roads, and not all states have big transit projects. We wanted to study a type of project that was common across states, so we took the bread and butter, resurfacing, as our case study.

Do we know anything about how infrastructure costs are related to different regulations at the state or federal levels, or to different political processes?

If you look at highway infrastructure, my co-author Zachary Liscow has a nice paper on the cost of road building over time in the United States. It ends in 1980 or 1990, because that's when we stopped building a lot of new roads, but the authors find a significant increase in cost per mile between the 1950s and the end of the century, even after controlling for all the variables they can – things like weather and geography. They also show that increases in labor costs don’t explain the bulk of the road building cost increase. Their main interpretation of this is that citizen voice is making it more expensive to build roads; there were a series of regulations in the 1970s that made it easier for people to get involved in the government process. That’s not necessarily a bad thing – neighborhoods can organize to prevent a road being built near them, or require more environmental review - but that greatly slows the process, which indirectly makes it more expensive.

Your most recent paper - Procurement and Infrastructure Costs - focused on the role of the procurement process in driving costs. You built a large database of state-level procurement rules and interviewed those working on projects on the ground. Can you start by giving a high-level overview on how the procurement process for US infrastructure projects work? And how this could increase costs?

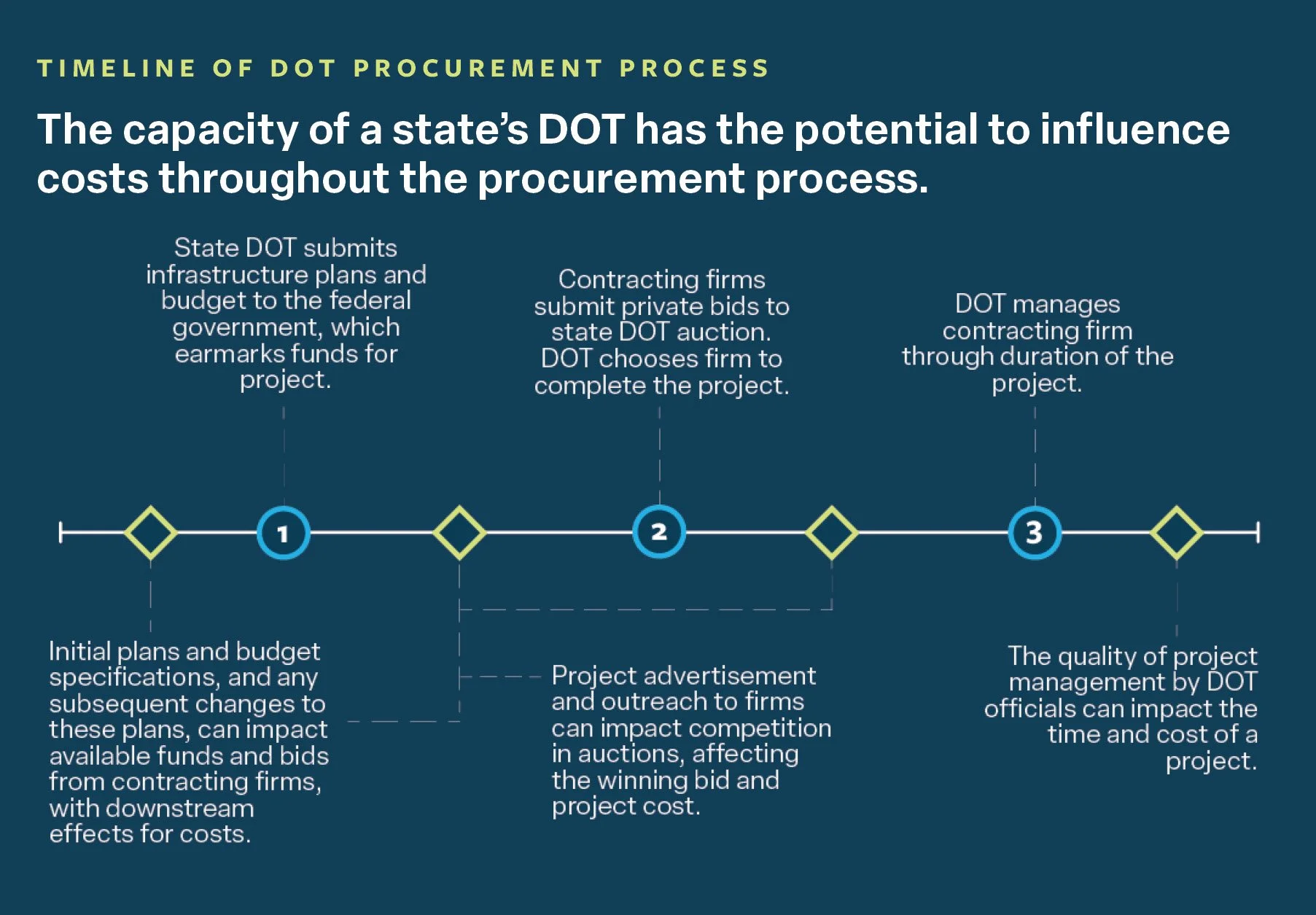

The basic way that it works is that each state DOT (who manage the majority of infrastructure projects)writes up a plan about which projects they want to complete in the next couple of years. They submit that plan, with a budget, to the federal government as an application for federal funds for infrastructure. They'll get some federal funds based on that, which are earmarked to those projects in the proposal. So a lot of money is coming from the federal government going to the state level to build and maintain infrastructure, and then states have their own sources that they complement this funding with.

At the next stage - the procurement stage - the DOT says, “We have this money to resurface this part of the highway – we're going to put out a call for bidders.” For the most part, the government is not the one building and maintaining infrastructure – the private sector is.

The state’s question is, “How do we find the right contractor for the job, at the lowest cost to the government?” So they'll run an auction, where all the prospective contractors look at the project plans and submit bids privately. The government then looks at all the bids; generally, they pick the lowest bid, and that's who will build the project. Along the way though, there are many inputs that can drive costs.

For example, before a project is even posted, engineers at the DOT estimate how much it's going to cost, and give very detailed plans to the contractor – because if the contractor doesn't know exactly what you want them to do, how are they supposed to bid on it? And the more detailed the plans, the better – because as you provide more details to the contractor, they have a better idea of exactly how much it's going to cost them, and they can make a more informed bid on the project. If the contractor has an incorrect expectation of what the project is going to look like, they break ground and things are not as they seemed; the contract has to be renegotiated, which causes delays and increases the project’s cost. So putting plans together is a big part of the job of the DOT, and is potentially where you could see costs increase.

Another decision that DOTs make is how to advertise the projects. How do you get people to bid on your project? Are you actually having all the contractors in the market that could potentially do the project?

Once the contractor wins the contract, they actually have to complete the work. Now, the DOT has to oversee and manage the private contractor on the project. Here, communication is really important – for instance, being quick to respond to changes that might need to be made to the plans or to the contract. Anything to avoid delays is potentially something that can keep costs down. Anything that has to do with permitting and traffic rerouting is where the DOT is going to get involved. So it's not simply, “we have a procurement auction and someone wins.” When someone wins, there's months or years of repeated interaction as the project is actually constructed.

What were some of your biggest findings from the survey and the review of state-level rules?

The motivation for the data collection exercise was that we couldn't say, in the aggregate, how much differences in procurement processes— how states procure projects — explain differences in costs. At the end of the survey, we had around 80 variables that we correlated with costs, – and very few of them showed any significant correlation. For instance, how do states differ in deciding how to throw out a bid? It doesn't seem like [they do] at all. The way I think about it now is that there are a lot of rules in the United States, and a lot of standardization across states.

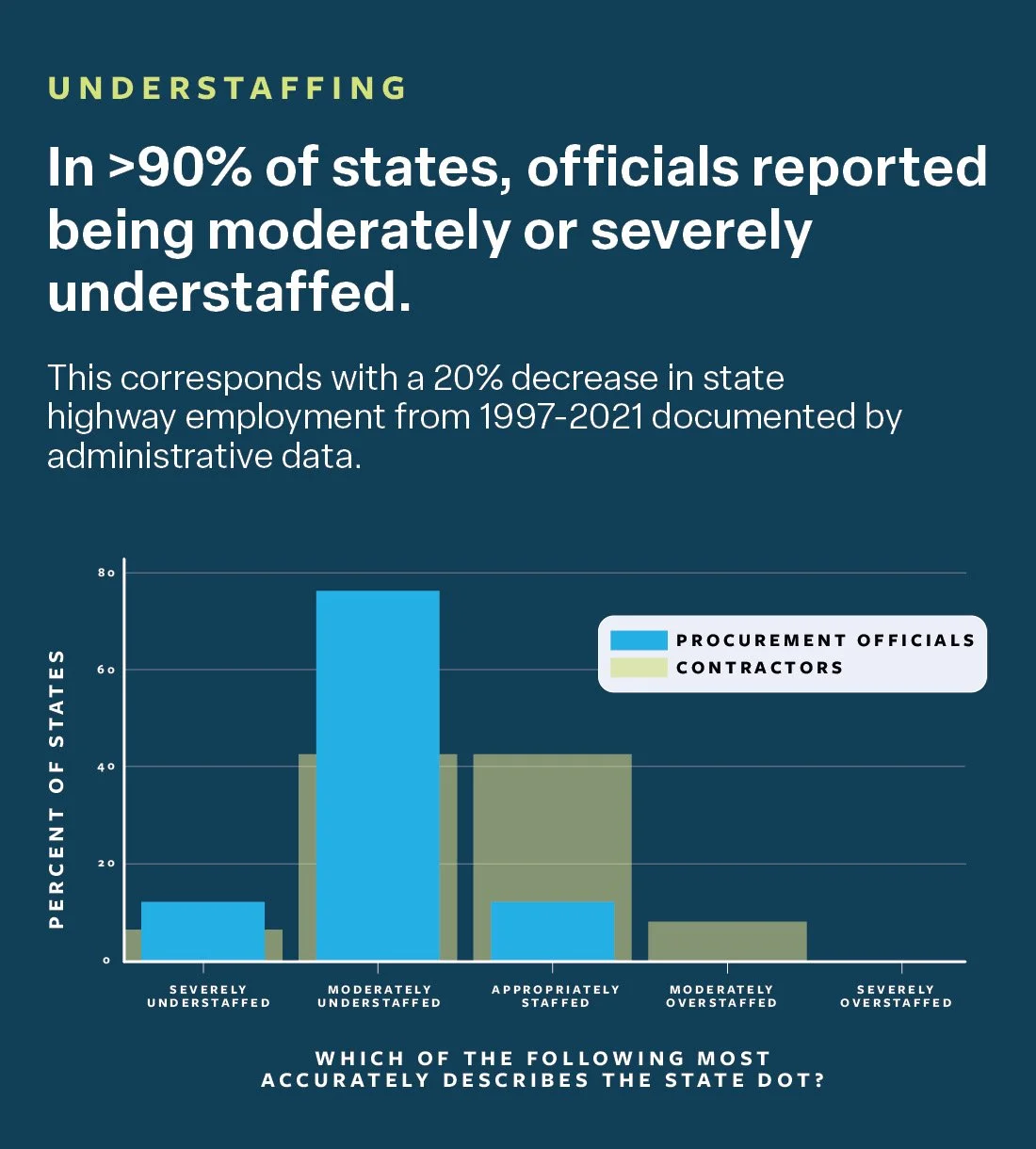

But the [variables] most correlated with costs [from survey and administrative data] were all about the capacity of the DOT, or the competition for the contract. So I think of it as inputs into the procurement process that matter – the capacity of the DOT, as measured by employment, employee quality, and things that are correlated with those two things, like plan specification.

Another factor seems to be competition in the market – how many contractors there are actually bidding on projects.

What I liked about the survey was that it featured free responses. So you can ask the DOT official, or ask the contractor, “What do you think drives costs?” “What do you think of your DOT colleagues?” “What do you think of the DOT procurement process?”

They're very descriptive about these issues. There are many state DOT engineers that are super knowledgeable on all of the rules. Because there’s so many rules, you have to be there for a while to understand all the ins and outs, and what to do in any given situation. If you're new, then you struggle with that. If a bunch of people retire, and we can't fill those spots, then engineers face this knowledge gap and have to learn from scratch.

Does California’s unique position as a state, and specific infrastructure procurement processes, present any challenges for external validity?

I think the capacity story is a universal one. We know from the survey that a lot of states are dealing with this. I talked to some industry groups when I was in New York, when we first started this project and, and they were saying the same things, even coming from outside of the DOT. So I don't think it's a California specific issue – it's just that California is kind enough to share detailed data with me.

Your new paper goes beyond correlations and focuses on how much the capacity of DOT staff impacts costs. It seems difficult to isolate the effect of specific staff members on the overall costs of these projects. Can you explain a bit about how you’re doing this?

Our plan is to do a fixed effects analysis, which is pretty standard in the literature. You see it applied to studies of teachers, judges – you know, how do you measure a teacher’s value added? Well, you look at all of the students a teacher has, and then students switch teachers, and you can measure what the teacher effect is. So the idea is to do that with the engineers who manage the projects.

This type of fixed effects analysis has been done in other procurement settings, mostly in developing countries, to try and understand how much a bureaucrat matters. What is interesting about our setting is that we have two levels of bureaucrat. We know who the person is that is managing the project – and they’re supposed to be managing the project from the inception of the project to when it is completed. They manage putting together the plans, doing the environmental review, dealing with permits – all this stuff that happens outside of the actual building of the road. But for each project, we also know the engineer on the ground, who’s managing the road building. Having these two layers in our setting will help us understand what matters more for driving costs.

Are there particular methodological challenges that come with studying infrastructure projects in this way? If so, how has your paper dealt with these challenges?

What’s difficult in our setting, which we're still struggling with, is that in any project, things can go wrong that are unobservable to the researcher – like, maybe it just rained for three weeks straight, and that's why it costs so much – not just because the engineer was doing a bad job managing the project. Examining many projects that the same engineer has worked on is an attempt to control for that. But if that's happening all of the time, it adds a ton of noise to the data, and that makes it a lot harder to measure the true value of the engineer.

The descriptions we have of the projects are also pretty short. There's a “project type” category, but I wish we knew more about exactly what each project entailed to be able to, to the best of our knowledge, say we're comparing apples to apples here. So that's something we're still working on.

Addressing this involves a lot of going back and learning more about how Caltrans categorizes projects – going into project plans and seeing what they look like, to see how much variation there is across types of projects.

The second part of your project investigates the impact of a program Caltrans has developed to increase staff capacity in local project management. Can you talk about the motivation behind this program, and describe some potential effects of a more or less centralized management process for these types of projects?

Caltrans has a program, the Local Assistance Program, which aims to help localities who have their own Departments of Public Works with some of their projects. Caltrans is interested in knowing how much that helps. One aspect they're interested in studying is having a Caltrans engineer oversee a project, instead of a local engineer. It's not clear in theory what effect that would have.

You might think the local engineer has local expertise, and maybe has a better idea of what the exact specifications need to be – and you'd think that the state isn't going to add much value there. On the other hand, if you think the state engineers have more experience just in general, maybe they've seen a particular type of project before that a local engineer hasn’t, it could help reduce costs. It's an interesting empirical question they want to study.

You can find two very similar looking projects, but one is managed by a state engineer, and one stays local, and compare them. We do that for many projects, and then we could dig into the mechanisms of why getting state support might help or or hurt. I could come up with good reasons in both directions, so I think that that's what makes it interesting. Maybe what we'll find is that sometimes it really works, and sometimes it really doesn't. I think it's a more general question in economics – how centralized do we want to do things? How centralized should we procure, not even roads, but say, pharmaceuticals? If the government was going to procure pharmaceuticals, you might think, the bigger the buyer the better, because they have a lot of buying power and can achieve a lower cost. But with roads, the amount of knowledge it takes, and the fact that there's supervision on the ground – all of these things make it much more complicated.

If procurement rules don’t seem to have a substantive effect on the cost and timeliness of infrastructure projects, what other policy tools might states use to address these issues?

I think that there are creative policies to be had on the labor market side of how to recruit high quality employees. It used to be that being an engineer for the state was a prestigious and well-paying position, but now the private sector dominates, in terms of wages, and state benefits are not what they used to be. That's more of a structural change related to government jobs versus the private sector.

The other thing that we haven't talked about as much is the contractor's market. Contractors complain there's not enough firms for competition on the subcontracting market. DOTs complain there's not enough competition on the primary contracting market. I think in many cases, firms exist that do this type of work, but perhaps don't know how to apply for government contracts and go through the process. In some situations, the forms that firms have to fill out are hundreds of pages long. One avenue for policy might focus on ways that the state can grow the market of contractors that take on public sector work. There are contractors out there that don't compete for government contracts, and we want to understand why. That’s a place where there's potential for more research.