In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, there has never been a greater focus on frontline workers. While much of the country continues to shelter in place, frontline workers are tasked with mounting the direct response to the pandemic as well as ensuring that essential government services are maintained. Frontline workers—many of them public sector employees—are crucial to an effective pandemic response, but these workers are facing exceptionally high levels of burnout and anxiety given stressful working conditions. Understanding what can be done to mitigate burnout amongst frontline workers is an increasingly urgent question for policymakers.

Faculty Director of The People Lab and O-Lab faculty affiliate Elizabeth Linos is well-placed to address this question. As a public management scholar and behavioral scientist, Linos’ research examines how to improve government using tools from both economics and psychology. In particular, she focuses on people in government, and through her work with The People Lab, works directly with governments to design and evaluate programs focused on improving strategies to better recruit, retain, and motivate public servants. Her research is motivated by efforts to understand and improve interactions between government workers and residents in order to identify ways to improve the responsiveness of government to its residents.

In this O-Lab Q&A, Linos discusses her latest research on frontline worker burnout as well as the shifting narratives and trends for frontline workers in the coronavirus era. She explains the important findings from her experimental study—one of the largest field experiments of its kind to-date—evaluating how to mitigate burnout and turnover among 911 dispatchers using low-cost, behaviorally-informed interventions. Finally, Linos discusses her own priorities for future research as well as the exciting potential for entirely new areas of research linked to frontline public sector workers.

Given the ongoing pandemic, there is more attention than ever on the role of essential and other frontline workers. Can you describe how you think about frontline workers in this context and how your research ties into these discussions?

Elizabeth Linos: I'm very grateful and optimistic that people have been recognizing the importance of frontline workers as essential workers. With the pandemic, obviously there are many people who can't shelter in place. Some of them we highlight, like health workers. Others we should highlight more, like people who work at grocery stores and gas stations, or who are collecting our trash. But there's actually a huge group of public sector workers who are keeping the trains running by going to work, and often we don't see them. This is an opportunity to highlight the importance of having an effective government workforce because, without them, we couldn't possibly have an effective covid response.

The work that I've been doing lately tries to understand not only what motivates frontline workers, but also what barriers they face to be able to do their job well. And that's led me into a lot of research around burnout and anxiety. I've focused on professions or occupations where we've seen really high turnover rates over the past few years, and where it's been really hard to hire enough people to deliver services. The level of burnout and anxiety amongst those groups was high before, but during covid, it's shockingly high. Right now, we're finding that sometimes anxiety rates are 20 times higher than under normal circumstances. This is a huge challenge not only for the current crisis, but also to ensure that we will have frontline workers in the next few years that are able to deliver services over time.

Why did you look at 911 dispatchers specifically?

Linos: The 911 dispatcher project came from government partners who asked me to work on it. When I first got the calls, I was working for the Behavioural Insights Team, which is a team of behavioral scientists that works with governments to help them use behavioral science to deliver better services. One question I kept getting from various cities was about 911 dispatchers: “They have really high levels of absenteeism. We can't keep them. They keep quitting. You say you're interested in people in government. Can you figure it out?”

“Feeling like people understand and value what you do seems to be highly correlated with lower levels of burnout. So, we started a project with 911 dispatchers across nine different cities to better understand why people were feeling burnt out and what we can do about it.

That kept happening, and after a while, I realized that this is a group of people who are really undervalued. In law enforcement, there's a lot of status placed on police officers in different settings. In society, we have a lot of respect for firefighters, but the people who actually pick up the phone when you call 911 are often less respected. Even in federal categorization, they're often considered call center workers, so they don't get a lot of the benefits and the privileges that emergency responders get. I've now found in my research that being undervalued actually is really important. Feeling like people understand and value what you do seems to be highly correlated with lower levels of burnout. So, we started a project with 911 dispatchers across nine different cities to better understand why people were feeling burnt out and what we can do about it. And that's really where this paper starts.

How were the studies designed and what were your results?

Linos: We did this project in collaboration with the Behavioral Insights Team as part of the What Works Cities Initiative. What we did was actually quite simple. I realized that a lot of the ways that we try to motivate public servants revolves around telling them how important they are to residents. What I have found is that if you've joined government because you want to help people—say you became a social worker because you want to help children or you join law enforcement because you want to help protect people—the actual day-to-day tasks that you're assigned to do don’t always mesh with that vision.

So I wanted to test a different way of thinking about impact that was not based on having an impact on residents. I wanted to focus on how people can have an impact on each other and how they can have an impact on their peers. What we set up was a system that was really low-tech, where we asked 911 dispatchers to share their experiences and their advice to other new dispatchers. Every week they got an email from their supervisor with a specific prompt that was behaviorally informed. It would be something like, "What would you tell a newbie about what it's like to be a 911 dispatcher?" Another week, it could be, "What are the characteristics of a good mentor and who has been a good mentor to you?"

“All of these nudges, these weekly emails, had the same underlying purpose, which was to prime 911 dispatchers to reflect on how they are connected to each other, how they can support each other, and how valuable they are to each other.

But all of these nudges, these weekly emails, had the same underlying purpose, which was to prime 911 dispatchers to reflect on how they are connected to each other, how they can support each other, and how valuable they are to each other. You don't need to get your status or your value from the police officer or from society. You can actually have an internal group, a group of 911 dispatchers, that has a strong professional identity and a sense of connectedness. And because we were able to do this in nine cities, this was really about building a professional identity outside of the team. Dispatchers were speaking to and hearing from other 911 dispatchers across the country, and I think that was part of why this was effective. For six weeks, they got these e-mails. Some people read the emails. Some people wrote about their experiences. Not everyone did. And that's, I think, an important part of how you set up these types of programs. And then we measured their levels of burnout before the program, right after the program ended, and four months later.

These were set up as randomized controlled trials, so we also had a control group, or comparison group, of 911 dispatchers during the same period in the same city that didn't receive the e-mails. Because we set it up as a randomized control trial, we know that any difference that we see either in burnout scores or other organizational outcomes for the people who received those emails can really be attributed causally to the program and not to other factors that were happening at the same time.

To our surprise, we found that not only did burnout go down but also resignations went down significantly. We saw resignations drop by more than half in the post-intervention period. We saw burnout scores go down by about eight points on the validated CBI (Copenhagen Burnout Inventory) scale. What that translates to is approximately the difference between being an administrative assistant versus being a hospital social worker in terms of the change in burnout. Now, I should say this is probably one of the biggest randomized control trials trying to reduce burnout, but it's still pretty small. The study included a little over 500 people. I think of this as a really interesting and promising pilot that we now can expand and try to replicate to make sure that the mechanism that we think is causing these effects is actually causing it.

“We found that not only did burnout go down but also resignations went down significantly. We saw resignations drop by more than half in the post-intervention period.

Can you talk about the mechanism in this kind of intervention?

Linos: Both in experiments that we've done afterwards and in some correlational survey work that we've done, we're really trying to tease out why this works. What is it about sharing your experience or feeling like you're connected with other people that causes burnout to go down? And it seems like we've learned a couple of things. For one, I consistently find that people who feel like they don't belong in public service or who feel like they're not connected to people at work show higher levels of anxiety, burnout, and fatigue. There's this really strong correlation that we find where there's something about feeling like you're part of a group of public servants that matters.

And we know this from other research as well. From private sector research, we know that one of the strongest predictors of whether or not you stay at a job is whether or not you have a best friend at work. So it's not new to think about social support as a really important part of people's work experience. What I think is newer is really thinking about belonging to a kind of an undervalued group in public service and seeing that as an important part of what makes people get up and go to work in these difficult environments. And we've seen it with correctional officers. We've seen it with health workers. We've seen it with obviously 911 dispatchers. We've also seen it across city employees.

It's a really important question because if we can figure out how to make people feel like they belong, we might have these subsequent effects on all these organizational outcomes that we care about, ranging from making sure people don't quit too early all the way to how they interact with residents. So what we think is happening is that feeling like you have someone to talk to and feeling like you're going to be understood by a group of people who understand what you're going through increases your sense of personal accomplishment and your sense that you can handle the difficulties that come your way at work. I also want to be clear about this. Obviously, your work environment in the more traditional sense are going to affect whether or not you're exhausted at work. Your work hours, your pay, whether your manager supports you—all of these things are clearly really important. But this additional force of feeling connected to people at work or feeling connected to public service seems to have an additional effect on burnout and anxiety, so that's really what we're focusing on in subsequent studies.

“If we can figure out how to make people feel like they belong, we might have subsequent effects on all these organizational outcomes that we care about, ranging from making sure people don’t quit too early all the way to how they interact with residents.

This research looks specifically at 911 dispatchers, but how does this work apply to other types of frontline workers?

Linos: We're still learning where this is applicable and where it isn't. It’s important to note that there's some fundamental level of connectedness that you would need for something like this to work. We are encouraging people to reflect on how they are connected to each other. And so, if things are really bad in a specific agency or there really is a toxic work environment, it's possible that a nudge of this kind is not enough or might even backfire. When you ask people to reflect about how they interact with their work colleagues, that can have anxiety-inducing effects if things are really bad. One thing that we need to still tease out in future research is under what conditions would something like this work.

The second thing we need to explore further is what type of frontline workers are most likely to be responsive to this. There, we are seeing frontline workers who feel more undervalued, or who feel like they're not understood by society at large, seem to have stronger effects. We've done some work with correctional officers, we've done work with 911 dispatchers, and we’re now doing some work with health workers. It's possible that this is more broadly applicable. We don't know yet. One thing that I'm going to do in future research is also look at social workers, teachers, and other types of frontline workers where we do see the same retention challenges but that look very different in terms of how they think about their own identities at work.

What are the major contributions of this paper to the wider literature on frontline workers in burnout?

Linos: I should start by saying that, even though burnout is really a popular term these days, there are decades and decades of really rich literature that looks at both the predictors of burnout and the consequences of burnout. I think what's different about this project and my future work in this space is that, rather than describing burnout, we've now moved into this second phase of trying to figure out what works in reducing it. And that's a whole other challenge. Bringing the rigor of causality to that question is where this study starts, but other studies will move this forward as well. Understanding burnout is step one, trying to figure out what works is step two.

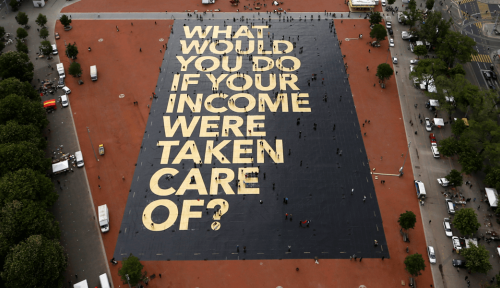

The main contribution here is that even something that is low-cost and behaviorally-informed might be applicable. Most of the thinking around burnout focuses on much bigger structural changes, such as changing the number of hours that people work or giving people more leave time. It’s thinking about the four-day work week if you're in the private sector or more autonomy over your job and your job design. A lot of the tools that we've heard of in the past are much more applicable to a private sector environment. You don't have a lot of say in many public sector frontline work environments about the specifics of your job, your job title, or even what shift you work on. What I'm excited about with this paper is thinking about something that works in an environment that has all the restrictions and limitations of a public sector environment. I think that's where the main contribution is, but again, I think we're still at the beginning of understanding how to mitigate burnout.

~THE STUDY SHOWS MEANINGFUL SAVINGS FOR ORGANIZATIONS DUE TO REDUCTIONS IN TURNOVER. SCALING THIS INTERVENTION TO ALL EMPLOYEES COULD SAVE A CITY WITH 100 DISPATCHERS MORE THAN $170,000 PER YEAR.~

What are some of the opportunities you see for more supportive workplace policies in the public sector, particularly given the attention to frontline workers over the last few months?

Linos: I think there are a couple of different areas that we can explore. One, obviously, is this idea of making sure people feel like they belong. We know now from surveys that we've done in a bunch of different cities and state environments that, for example, employees of color are less likely to feel like they belong in public service when things go badly. There are many ways that we can think about belonging and making sure that people feel like they belong and are supported at work that might have effects on burnout. There's also a whole separate category of projects around supervisors and thinking about what supervisors can do differently to make sure that their staff feel heard. For example, with correctional officers, Amy Lerman has shown that experiencing violence and the threat of violence significantly increases anxiety— but what she and others have found is that if you have a boss or supervisor that you feel is going to have your back, that link between experiencing violence and anxiety is mitigated.

One question that we haven't tackled, but which I think is important for future research, is how society at large views frontline workers. It doesn't help when you have an administration that talks about bureaucrats as though they're the enemy or about draining the swamp. There's a whole history of talking about government workers as though they are lazy and corrupt. I'm hoping that with this crisis and with future crises, we're realizing more and more how inaccurate that is and how damaging that can be, not only in terms of how current public sector workers feel and how motivated they are, but also in terms of our likelihood of getting talent into government in the future as well. I think those areas are the ones that we need to explore a little bit more carefully in the future.

“Employees of color are less likely to feel like they belong in public service when things go badly. There are many ways that we can think about belonging and making sure that people feel like they belong and are supported at work that might have effects on burnout.

Your previous research took place prior to the start of the pandemic. What are you currently working on and what are some of the preliminary findings on frontline worker burnout that you are seeing?

Linos: Because we've set up really good partnerships with government partners through The People Lab, we were able to quickly survey a lot of employees in the midst of the pandemic. There are a couple of things that we've learned. One is that people are ready and willing to talk about mental health in a way that I think is really surprising. We're seeing some patterns that we haven't seen in previous research. For example, Asian-American employees seem to be reporting much higher levels of anxiety than in previous surveys that might have to do with the racism surrounding the coronavirus.

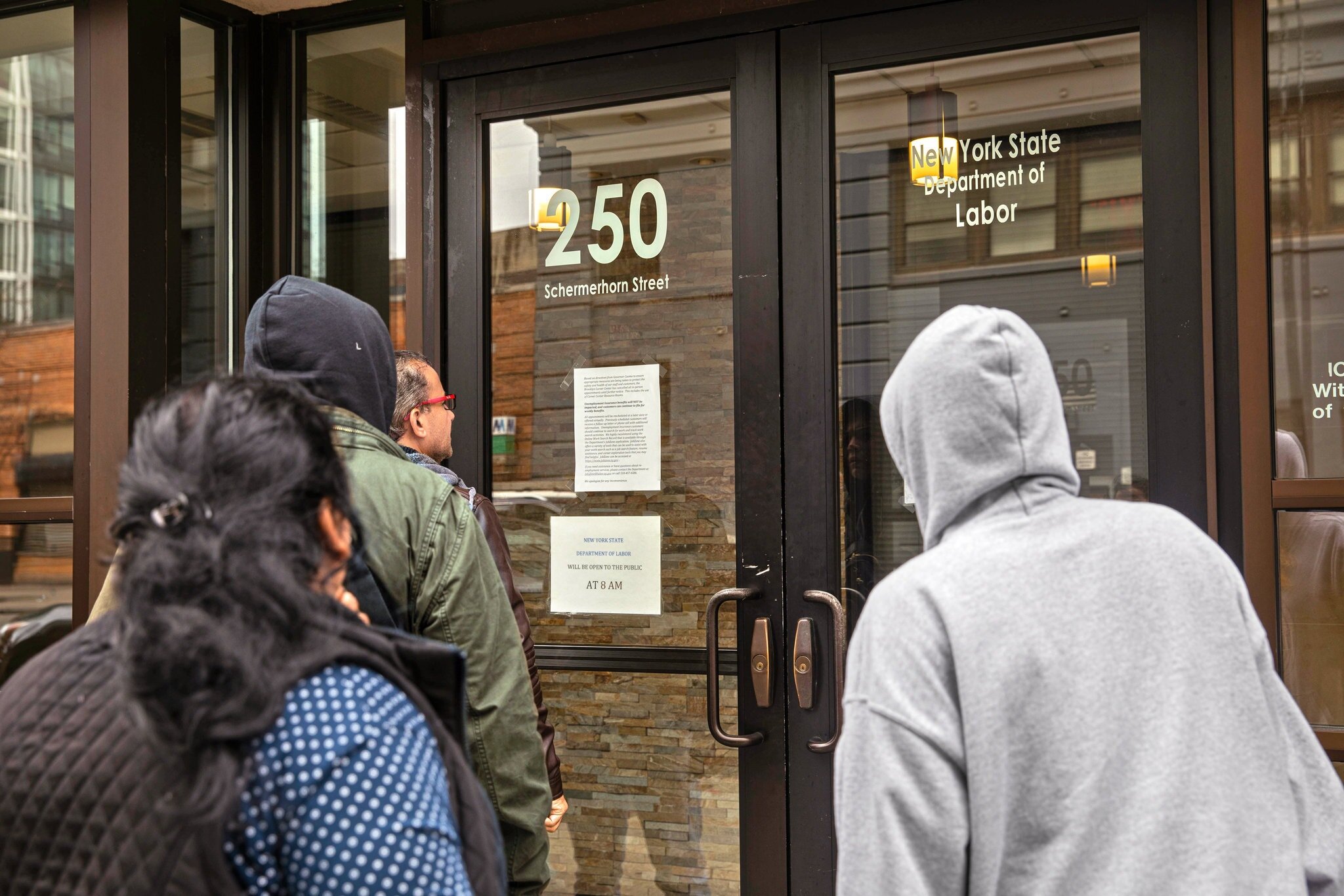

Next, we're also seeing a lot of really saddening levels of burnout and anxiety among frontline workers. Some of this has to do with government workers feeling like they need to protect their families and their loved ones. Some of it has to do with feeling like they need to meet the needs of their clients. For example, if you're working in unemployment insurance, a lot of the anxiety has to do with feeling like you can't keep up with the demand for more unemployment insurance claims. And then there's a third category that has do with financial insecurity, which I think is often overlooked for government workers. Being a government worker today is not like being a government worker a couple decades ago. There is not as much job security, pay is not as good, pensions are not as good, and so people are really worried about losing their jobs. And many of them have been furloughed and are going to lose their jobs during this pandemic.

If you put all these things together, you have workers who often can't stay home, so they can't really protect their families from the pandemic. They're worried about getting sick and getting their loved ones sick. They're also worried about increasing and changing demands on their work. For example, we have people who worked as social workers or caseworkers in a job center that are now running homeless shelters, meaning you’re changing your job description overnight, while still being worried about losing your job. So it's no wonder that frontline workers are struggling on the anxiety front. I think it's something that we really need to pay attention to and worry about investing in, if we're going to get out of this covid recovery in any effective way.

How do you think that the pandemic has changed the way society and the broader community outside of these occupations think about frontline workers?

Linos: In previous decades, people have talked about government bureaucrats as a negative drain on society, but I do see a changing narrative. When we had furloughs in recent years, people were highlighting the government workers who were going to soup kitchens and weren't able to pay their bills in national media outlets. For the first time, the national sentiment was that we need to support our government workers. The narrative I was hearing was that, whatever the politicians are doing, we need our permanent public sector workforce to hold down the fort and deliver services. I think a lot of this change in narrative has to do with who we think of as competent to deliver services. I don't know how that's going to change over time, but to me, it's exciting that people are starting to recognize and thank frontline workers for keeping the country running. That's really what a bureaucracy is made for. This is why, in the U.S. and in a lot of other developed countries, we have a permanent civil service that is different from the political administration. It's at moments like these that we might recognize how important a functioning democracy is to our lives.

“Being a government worker today is not like being a government worker a couple decades ago. There is not as much job security, pay is not as good, pensions are not as good, and so people are really worried about losing their jobs.

Given the context of a changing narrative around frontline workers, what are your priorities for future research in this area and behavioral science interventions more broadly?

Linos: I'm really interested in not only better understanding what works in supporting workers, but also in measuring whether or not this has an effect on the services they deliver. It's a theoretically justified hypothesis that says if you have more engaged frontline workers, you're going to be able to deliver better services, but we don't actually have good causal evidence that that's the case. I think it's really important to push the research in that direction, because if burnout affects whether or not frontline workers are able to deliver better or more equitable services or we show that there's less variability in their decision-making, then that really changes the importance in investing in that government workforce. That's what I want to study next.

For example, if you have a less burnt out frontline worker, do we see less bias? Will that frontline worker deliver services that are less variable based on the characteristics of the resident who they're interacting with? Let's imagine a world where you have less burnt out teachers. Is that going to affect the black-white test score gap? When we think about social workers, if they were less burnt out, are they able to make more equitable decisions around child removals? If we can actually look carefully and rigorously at the causal pathways between worker stress and burnout and resident experience, we might tap into a whole new world of research about how to improve government.